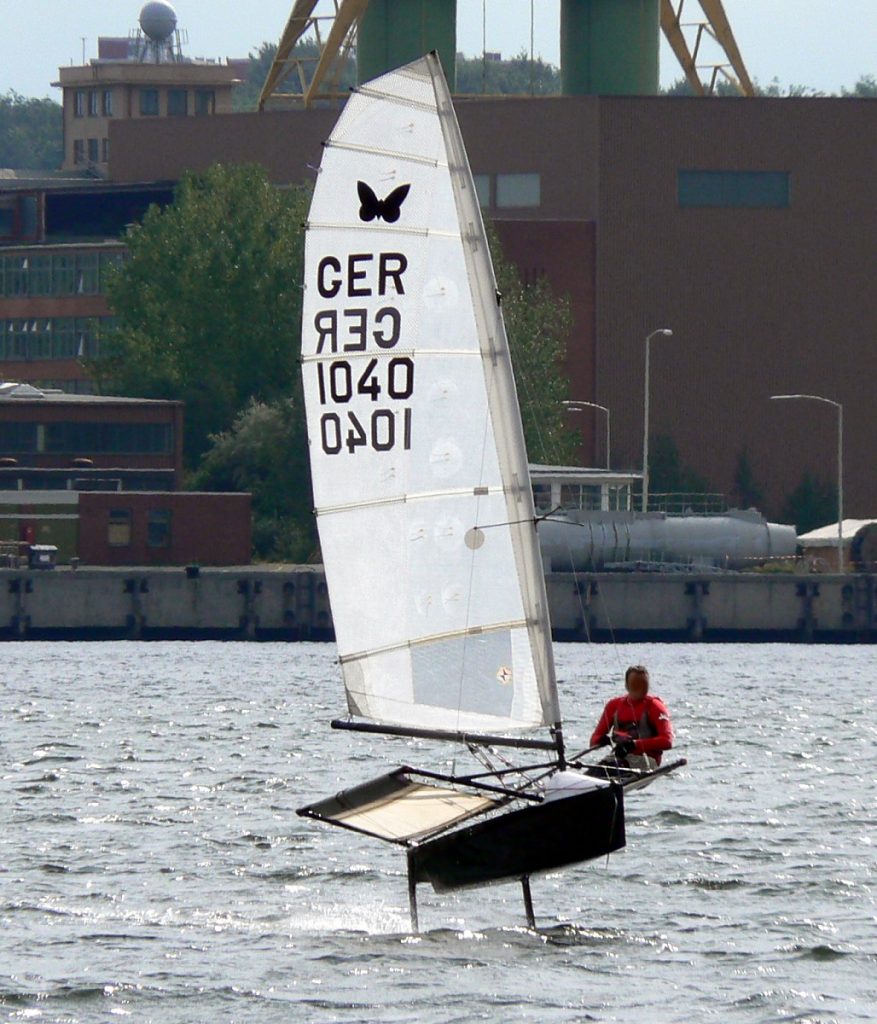

Wikipedia comments on the Moth class, “Originally a small, fast home-built sailing boat designed to plane, since 2000 it has become an expensive and largely commercially-produced boat designed to hydroplane on foils. The pre-hydrofoil design Moths are still sailed and raced, but are far slower than their foiled counterparts.”

There have been many iterations of the Moss dinghy, with the exact number dependent on how they are counted. First, it began life in Australia in 1928 when Len Morris built a cat rigged = single sail, wooden scow = a flat-bottomed boat with a horizontal rather than a more common vertical bow. It was hard chined = with a sharp change in angle in the cross section of a hull, 3.4 m long, with a single 7.4 m2 mainsail. A second iteration emerged in North Carolina in 1929, with a 6.7 m2 sail, on a somewhat shorter mast. In 1933, The Rudder, an American boating magazine, published an article about the American Moths. A third iteration came about in 1932, when a British Moth class was started. This was a one-design, which meant that there could be very little variation between the boats. One designs are used in competitions so that winners can be distinguished on the basis of sailing ability, rather than in boat characteristics.

The fourth iteration was initiated with the Restricted Moth of the 1960s and 1970s. With few design restrictions, individuals were allowed to modify their boats. This allowed the class to develop and adjust to new technology and materials. An International Moth arose in Australia and New Zealand.

The Europa Moth, which became the Olympic Europe dinghy, can be regarded as a fifth iteration. This was followed by a sixth iteration, in the form of a New Zealand Mark 2 Scow Moth, in the 1970s. Finally, a seventh iteration emerged with the International Moth, a fast sailing hydrofoil dinghy with few design restrictions.

Most people who choose a Moth do so because it is a development class. In much the same way that there are two types of motorsport enthusiasts, those who want to keep their vehicles stock, and those who want to modify it. The Moth appeals to those who want to modify their boat. There are plenty of other one-design classes, some designed for racing, others more suitable for cruising, for sailors without genes that demand they experiment, and take risks.

The Moth of the 1930s was a heavy, narrow scow that weighed about 50 kg. Today’s foiling moth has a hull weight of under 10 kg. During some periods wider skows without wings have been popular. Now, hulls are narrow and wedge-shaped, but with hiking wings stretching to the maximum permitted beam. Sail plans have evolved from cotton sails on wooden spars, through the fully battened Dacron sails on aluminum spars, to today’s sleeved film sails on carbon spars.

While foiling moths are mainly used in protected areas, they can also be used offshore. On 2017-01-21 Andy Budgen sailed Mach 2 a foiling International Moth Nano Project to complete the 60 nautical mile (nm) = ca. 111 km (1 nm = 1852 m) Mount Gay Round Barbados Race at a record pace of 4 hours, 23 minutes, 18 seconds, to established the Absolute Foiling Monohull record.

In 2021, the much larger 75 feet = 23.86 m foiling AC75 monohulls were competing. First, the Prada Cup series was held to determine who would challenge New Zealand in the America’s Cup. It ended with Luna Rossa Prada Pirelli/ Circolo della Vela Sicilia’s Luna Rossa defeating American Magic/ New York Yacht Club’s Patriot and Ineos Team UK/ Royal Yacht Squadron’s Britannia. Speeds were regularly over 50 knots = 92.6 km/h = 25.7 m/s = 57.5 mph. In the subsequent America’s Cup, Emirates Team New Zealand/ Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron’s Te Rehutai defeated Luna Rossa, to retain the cup. Here is a 10 minute summary of the last race. This video will also show the massive size and speed of these vessels.

Readers may, at this point, wonder why this weblog post is being written, especially when this writer has no interest in sailing such a vessel. He would only be interested in helping to make one for others to use and enjoy. The typical person who could be interested in this, is an inmate at a Norwegian prison, perhaps this unidentified person who drove at 288 km/h = 179 mph, through a tunnel, and bragged about it on social media. Working with cutting edge technology, and sailing at the limits this technology allows, should be a perfect combination of activities for such a risk-oriented person. The advantage of sailing is that it doesn’t put other people in danger, although I would want to have a high-powered rigid inflatable boat (RIB) available during test runs, to rescue this person when (rather than if) he capsizes.

Unfortunately, I don’t expect the prison system to welcome this suggestion. They seem to think that having inmates make pallets will in some way create law-abiding citizens. It won’t. A previous weblog has discussed Flow as a means of motivating inmates.

Further information: International Moth Class Association, Mach 2 Boats, Mothmart (the International Moth marketplace).

I see your point about offering risk-oriented people a means for being able to achieve the thrills they seek without endangering others. I suspect the cost would be too much for the prison system. Kite surfing and snow kiting might be a cheaper alternative.

Still, I have to say that it would be sad if the noble moth, that one-design dinghy, which enabled beginning sailors to test their skills on an even basis against others, has truly become a relic of the past.

Thank you, Donna. Sometimes facts become too complex, so that one tries to simplify an issue. In terms of a foiling Moth, some of that additional information was related to having inmates learn to make Moths, so they become proficient constructing products incorporating carbon fibres. Advantages include high stiffness, high tensile strength, low weight to strength ratio, high chemical resistance, high temperature tolerance and low thermal expansion. These properties have made carbon fibre very popular in many areas, but they are relatively expensive, compared with similar glass based fibres.