Brigand Brewer continues his investigation of Cascadian poets, this time looking at the spiritual in the landscape. Most people referenced in the text are teachers or students taking Cascadia College’s Innovative Cascadian Poetry course.

Joseph Campbell’s, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, is a good starting place to understand the relationship between a poem and its landscape. Within the monomyth – poetic or otherwise – a hero (m/f) undertakes a single supernatural and archetypal journey into the landscape; the landscape being home to innumerable heroes, and some unimaginable number of archetypal journeys.

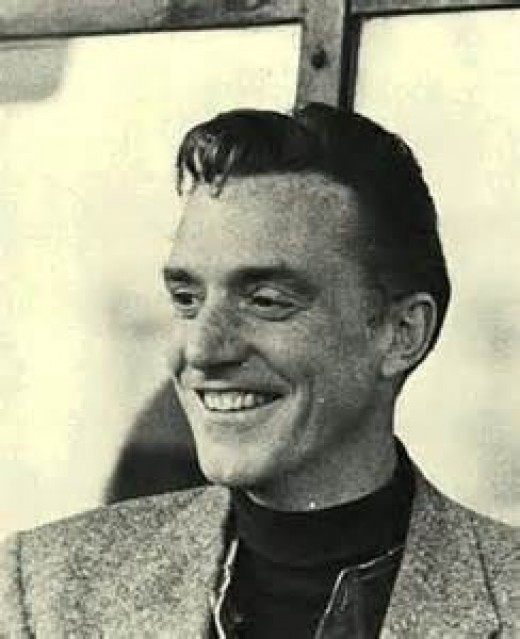

With respect to Lew Welch’s poem, Wobbly Rock, I appreciated Joe Chiveney’s reference to Gunter Nitschke’s explanation that the garden of Ryōan-ji does not symbolize. Finally, we have an artifact representing the non-symbolic. The qualities incarnated include materiality, location, abstraction, multiplicity, composition and functionality. Like a fiery orator rousing a crowd to rebellion, this Zen temple garden at Kyoto incites the visitor to meditation.

Greg Bem questions the concept of value. I am tempted to reference Oscar Wilde’s “Lady Windemere’s Fan” where Darlington defines a cynic as ‘a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.‘ Perhaps we are all cynics unable – in this material world – to appreciate the beautiful and orderly chaos that sustains our biological existence. Perhaps, a spiritual realm encountered after death will reveal a fuller meaning of the experiences that constitute a life.

Michelle Schaefer interprets “I have travelled, I have made a circuit….. When I was a boy” as an acknowledgement of the past as sacred. Then she goes on to add that every moment is sacred, as shown in “and now all rocks are different and all the spaces in between. Which includes about everything. The instant after it’s made.”

I appreciated Brent Schaeffer’s classification of the poems being discussed.

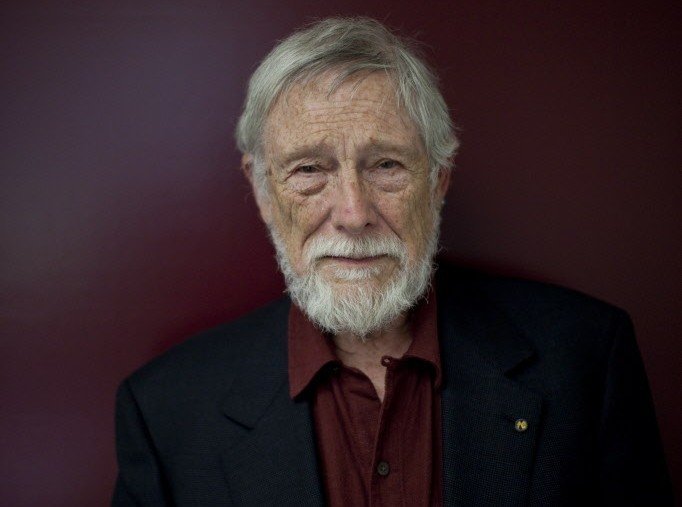

Soudough Mountain Lookout

Mengyu Li presents two of the key lines in Philip Whalen’s Sourdough Mountain Lookout:

BUDDHA: “All the constituents of being are

Transitory: Work out your salvation with diligence.””

The confluence between the passivity of meditating at the garden of Ryōan-ji and the world of restrained action at the Sourdough Mountain lookout is that everyone, in fact – every organic life form, is marching irrevocably, one day at a time, towards its ultimate death. Buddha suggests that our salvation, perhaps more understandably our status or situation after death, is dependent on our actions while we live. It will be too late to regret or to repent for our mistakes after we have left this organic world!

Carol Blackbird Edson notes that she experiences “a resonance of a changing consciousness” in the poems and commentaries selected. My understanding is that she regards the poems, despite their temporal and cultural limitations, as maps to explore the Cascadia bioregion, allowing the reader to enter into deeper relationships with primal nature found therein, and to gain a better understanding of themselves. I’m not quite sure how primal nature differs from other forms of nature, but that is one of my limitations.

Michelle Schaefer comments, “… our bodies are as sacred as our surroundings and they interact together.” I’d like to respond to this by bringing up the Baha’i concept that the essence of human identity is a rational and immortal soul, with the body being a temple temporarily housing the human spirit.

Brent Schaeffer adds to an understanding of the poem with, “Whalen’s exploration of ‘sacred’ is the folkloric/bildungsroman idea of returning to where you are, but seeing it different again for the first time. That only after touching the sacred can we see that our ‘mundane’ has always been sacred.”

Things to do …

We have all had an opportunity to write our own “Things to do …” poem. One non-poetic of Gary Snyder’s poem is that it provides a template that anyone can follow. The real advantage of this form is that it allows a juxtaposition of events that break with chronology. Michelle Schaefer comments on the line, “Do pushups. Sew up jeans. Get divorced” I am not sure that I agree with her that these represent sacred moments, even if I do admit that they provide insight into human vulnerabilities.

Oceans

In Wobbly Rock, Welch refers to the Pacific Ocean with the lines:

“I like playing that game

Standing on a high rock looking way out over it all:

“I think I’ll call it the Pacific”

Wind water

Wave rock

Sea sand

Thankfully, Welch makes no mention of the Atlantic, which is a foreign intrusion into Cascadia. In contrast, Whalen makes no mention of the Pacific, in Sourdough Mountain Lookout, but does mention the Atlantic, with these lines:

“Everything else they hauled across Atlantic

Scattered and lost in the buffalo plains

Among these trees and mountains “

Oceans are important in terms of our sense of identity. One can regard a continent in its uninhabited state as a succession of barriers, inhibiting movement. An ocean is a flat surface, encouraging movement. Admittedly, storms happen, and there is a need for some form of propulsion. Oceans connect people. The connections may be good (trade?) or bad (war), but mostly somewhere in between.

I have difficulty using the word Pacific in creative works. It invokes a feeling of alienation. Originating with Ferdinand Magellan, who first used it in 1520, finding calm waters after rounding Cape Horn in a storm.

Teresa Lea Schulze brings up the point that, “We are shaped by what is around us…. Humans may think they are unique, but we are connected to all around us. Poems and poetry strip away the ‘over word usage’ and uses the minimal amount to convey the largest picture…” One of the most effective ways we have of conveying the largest picture is to use names. Yet, the name Pacific is presenting a false image – peacefulness. Peaceful is not the essence of this vast ocean, as can be attested by countless sailors. Cascadians have managed to find an appropriate name for the Salish Sea. I hope they will also find an appropriate name for the Ocean that touches their shore.

Markers of Time

As seen in the poems studied this week, places are sacred or, at the very least, have a spiritual component. Just as places in the Cascadian bioregion function as markers of place, so too do events function of markers of time. As the world experienced on 18 May 1980, with the explosion of Louwala-Clough (Mount Saint Helens), Cascadia is an active participant in the Ring of Fire. This event was one of the most important regional time markers. A larger eruption 500 years earlier (1480) was another time marker.

I’d like to thank all of the people who posted before me. They have given many ideas to reflect on.