On 2014-02-20, Russia invaded Ukraine, and conducted a war that lasted until 2014-03-26. By 2014-03-16, Russia had succeeded in its stated aim, to annex the Crimean peninsula. Eight years later, almost to the day, on 2022-02-21 Russia officially recognized the two self-proclaimed separatist states in the Donbas, and openly sent troops into these territories. On 2022-02-24, Russia invaded Ukraine, the start of Putin’s war, or the second Russian invasion of the Ukraine this millennium.

Previously, I have written two post about this topic: In 2022 in a post titled Ukraine and in 2023, in a post about a democracy tax. This is a third weblog post that mentions Ukraine. I tried to use something resembling logic. This has proved illusive, and beyond my capabilities. My conclusion is that there can be no logical starting point, because war (and every other form of violence) is not a logical/ rational action. It cannot be understood logically.

Should I have to select one film that explains the current situation in Ukraine, I would choose Maidan (2014). It was directed by Sergei Loznitsa (1964 – ). I find Loznitsa an interesting director because of his background. He graduated from Kyiv Polytechnic Institute as a mathematician in 1987. Then he worked at the Institute of Cybernetics on expert systems. He also worked as a Japanese translator. Then he studied cinematography.

In the early 1960s, there were ample opportunities to reflect on violence. In October of 1962, there was the Cuban missile crisis. I lived about 165 km/ 103 miles from the American nuclear submarine base at Bangor, near Bremerton, in Washington State. If at the time I had known how close we lived to it, I probably would have been more worried. As it was, numerous people built bomb shelters adjacent to their houses, in New Westminster.

Perhaps I would have been more afraid if I had devoured On the Beach, either in the form of the novel (1957), written by Nevil Shute (1899 – 1960), or the film (1959), directed by Stanley Kramer (1913 – 2001). Both show the horror of nuclear war.

Discounting television comedies such as The Phil Silver’s Show aka (Sargeant) Bilko (1955 – 1959), McHale’s Navy (1962 – 1966) and Hogan’s Heroes (1965–1971), there have been few serious war series in the 1960s and 1970s. An exception was the The Gray Ghost (1957 – 1958), that portrayed the American Civil War from a Confederate perspective.

My first cinematic exposure to the violence of war, that had an impact on me, was probably Lawrence of Arabia (1962). I found it a disturbing film, not just because of the military actions it portrayed. It was morally vague, and depicted a person with psychic challenges, he is incapable of overcoming. I reflected on it, but not too much to keep my sanity. It was directed by David Lean (1908-1991), who had previously directed The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), although I only watched that film considerably later.

Deeper reflections on violence began 58 years, 3 months, 3 days = 3 040 weeks = 21 280 days > 500 000 hours > 30 million minutes > 1.8 billion seconds earlier than the start of this second invasion of Ukraine. On 1963-11-22, the day John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917 – 1963), the American president, was assassinated. The date is etched permanently into my brain, and marks an event that started my radicalization. Less than a month before, I had celebrated my 15th birthday, I was in grade ten, the youngest person in my class, having been born on the cut-off date that allowed me to start school in 1954.

Prior to Kennedy’s assassination, I was conventional. For example, I would fire five rounds of 0.22 caliber bullets, at the rifle range in the basement of Vincent Massey junior secondary school, after finishing band practice. Since then, I have not fired a weapon.

At the time of that assassination, people just a few years younger may not have been aware of the significance of it. People, just a few years older, may have already made a commitment to a particular world view. For me, it called into question the use of violence to resolve disputes. Gradually, I began to question the Vietnam war, war more generally, then other forms of violence. In part, it comes from examining the brutality of many other wars, notably the American Civil War, the Crimean War, the Boar War, the First World War. In part, this was aided by a fellow student, Steve Scheving, who kept meticulous statistics about casualties in the battles of the American Civil War.

Of the American Civil War films, one of the most respected is Shenandoah (1965), directed by Andrew V. McLaglen (1920 – 2014). Admittedly, it is sentimental, but it does raise a number of humanitarian themes. Some regard it as an anti-war film, which made it appealing to many draft-dodgers and others, facing the Vietnam war.

Then there are novel/film combinations that offer a means of understanding war. An understanding of the first world war can come from Im Westen nichts Neues = Nothing New in the West (literal) = All Quiet on the Western Front, English translation title (1929) more a psychological study looking at physical and mental trauma, as well as social detachment. It was written by Erich Paul (later his middle name was replaced by Maria) Remarque (1898 – 1970). Several film versions have been made, including the first one released in 1930, directed by Lewis Milestone, born in Moldova as Leib Milstein = Лейб Мильштейн in its original Russian (1895 – 1980).

The anti-war novel and film, set in the first world war, that I cannot recommend to anyone because of the horrors it contains, is Johnny Got His Gun. Blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo (1905 – 1976) wrote the novel in 1938, and directed the film version in 1971.

My timeline proceeds more cautiously through the Second World War because both of my parents served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, at that time. I find it impossible to condemn anyone fighting in a war defined by my parents as justified and necessary. I am too damaged to objectively reflect on this war, and find myself quoting, yet again, from The Go-Between (1953) by L. P. Hartley, (1895 – 1972): “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.”

I learned that romance and comedy could be used to hide the horrors of war. For example: James Michener (1907 – 1997) wrote a collection of short stories, Tales of the South Pacific (1947), from which the musical South Pacific (1949) theatrical production emerged, as well as the film version (1958), directed by Joshua Logan (1908 – 1988). Both of these featured music by composer Richard Rodgers (1902 – 1979) and lyricist-dramatist Oscar Hammerstein II (1895 – 1960).

I have a greater appreciation of Catch-22 (1961), the satirical novel by Joseph Heller (1923 – 1999), and the black comedy film from 1970, directed by Mikhail Igor Peschkowsky, better known as Mike Nichols (1931 – 2014).

I have allowed myself to see Schindler’s List (1993) and Saving Private Ryan (1998), both directed by Steven Spielberg (1946 – ).

Comedy also dominated the Korean war. The best example is M*A*S*H, subtitled, A novel about three army doctors (1968) by Robert Hooker, the pseudonym of Hiester Richard Hornberger Jr. (1924 – 1997), and the film (1970) directed by Robert Altman (1925 – 2006).

It is also easier to find fault with events in more distant places. It took me much longer to confront my own racism and other prejudices, and the genocide that took place in British Columbia. As an immigrant, it is easier for me to see contradictions in Norwegian society that Norwegians can’t admit to. Much of this has to do with religion. From my perspective, Norway only reluctantly allows freedom of religion, and has not fully recognized the violence sanctioned by its own state designated religion, particularly against the Sami people, but also others who did not think conventionally.

It was easier to condemn events in Algeria, Czechoslovakia, Chile and Korea, to name four countries on four continents, that people might suspect were randomly selected. They weren’t, for films have had a significant impact on my perception of the world, and of war. In these cases, respectively: The Battle of Algiers = La battaglia di Algeri, (1966) directed by Gillo Pontecorvo (1919 – 2006) ; Closely Watched Trains = Ostře sledované vlaky (1966) directed by Jiří Menzel (1938 – 2020); missing [sic](1982) directed by Costa-Gavras (1933 – ) although I am much more appreciative of Z (1969), which is about the assassination of democratic Greek politician Grigoris Lambrakis (1912 – 1963); The Manchurian Candidate (1962) described as a neo-noir psychological political thriller film, directed by John Frankenheimer (1930 – 2002).

There have been numerous films made about the Vietnam war, including: 1) Apocalypse Now (1979), directed by Francis Ford Coppola (1939 – ), loosely based on the novella Heart of Darkness (1899) by Joseph Conrad, born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski (1857 – 1924). Here, war is explored as an exercise in futility and as a catalyst for a descent into madness; 2) The Deer Hunter (1978), directed by Michael Cimino (1939 – 2016), focused on realism and the psychological destruction of individual participants. Many of these films are difficult to watch. This applies to most war films made after 1970. 3) First Blood (1982) was directed by Bulgarian-Canadian Ted Kotcheff (1932 -) and was filmed in and around Hope, British Columbia. Damaged Vietnam veteran John Rambo searches for an old friend in a small town but is harassed by the sheriff until he reaches his breaking point. Rambo reverts to his military mindset. 4) Kotcheff explored the Vietnam war very differently in Uncommon Valor (1983), with a focus on prisoners of war (POW), and people missing in action (MIA).

A Baha’i perspective on war.

A documentary about World War One, The Man Who Shot the Great War (2014), has had the greatest spiritual impact on me. I often reflect on the souls of men who have been conscripted, and ordered to kill other men. This war killed 37 million soldiers. George Hackney (? – 1977) was a Belfast sniper, and photographer. While unofficial photographs were illegal, his were allowed. George was also a Baha’i.

The Baha’i perspective is that no person is condemned to an eternity in hell or in heaven. Instead people continue their spiritual journey they began in their earthly life involving a greater spiritual understanding. I expect George found solace in this message.

In October, Baha’is celebrate the births of its twin profits, Bab (1819 – 1850) and Baha’u’llah (1817 – 1892). While its prophets may have their origins in Iran, Baha’u’llah was ultimately exiled to Akko/ Acre, in today’s Israel. This exile is why the Faith’s headquarters are located in nearby Haifa. I have been on pilgrimage to Haifa three times, but feel no need to visit a fourth time.

This month, the world has witnessed atrocities in Israel as well as the Gaza strip. Baha’u’llah has written on war, and come with recommendations for achieving world peace, in two documents, that are often quoted.

“Be united, O concourse of the sovereigns of the world, for thereby will the tempest of discord be stilled amongst you, and your peoples find rest. Should any one among you take up arms against another, rise ye all against him, for this is naught but manifest justice.” Gleanings, p. 254.

“The time must come when the imperative necessity for the holding of a vast, an all-embracing assemblage of men will be universally realized. The rulers and kings of the earth must needs attend it, and, participating in its deliberations, must consider such ways and means as will lay the foundations of the world’s Great Peace amongst men. Such a peace demandeth that the Great Powers should resolve, for the sake of the tranquillity of the peoples of the earth, to be fully reconciled among themselves. Should any king take up arms against another, all should unitedly arise and prevent him.” Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, pp. 30-1.

Needless to say, I am not impressed with the various rulers of the world uniting to further peace. As I approach 75 years of living on this planet, I reflect once again, much as I did in the late 1960s, on how countries are willing to sacrifice their most important resource, young people, in needless wars.

I further reflect on how countries, especially the United States through the Marshall Plan, were willing to invest in the reconstruction of Europe, which provided the basis for Germany, and many other countries, to prosper. The US, Israel and the many oil-rich Middle Eastern countries have been unwilling to invest in the West Bank or the Gaza strip, to ensure its Palestinian residents could prosper.

Al-Nakba (1996) is a documentary film by Benny Brunner (1954 – ) and Alexandra Jansse (1956 – ). It presents insights into past events in Palestine/ Israel that continue to shape current events. It is based on the book, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949 by Benny Morris (1948 – ), an Israeli historian. The film title refers to catastrophic events in 1948 forcing, an estimated seven hundred thousand Palestinians into exile and poverty, while Israelis, could create and prosper their own state.

This Israeli perspective is portrayed in the Leon Uris (1924 – 2003) novel, Exodus (1958), which was made into a film directed by Otto Preminger (1905 – 1986) in 1960.

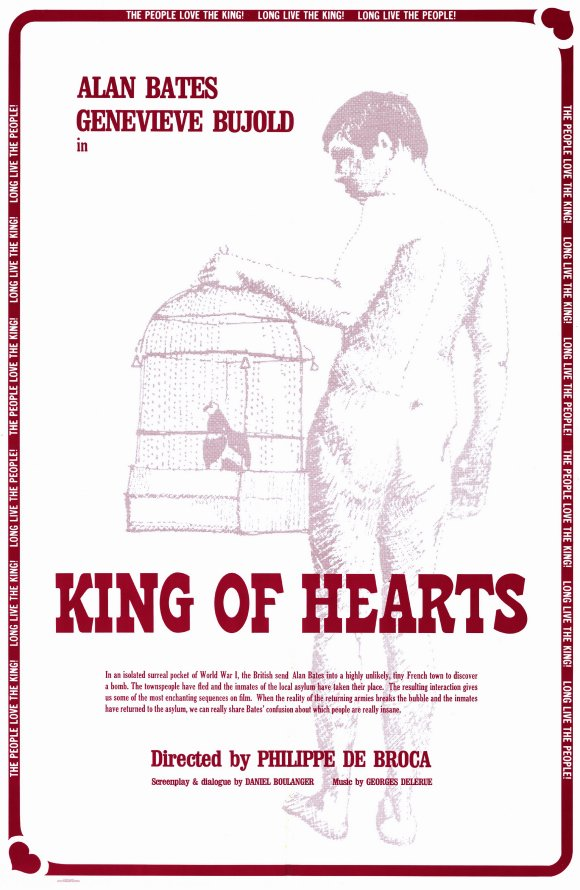

Perhaps the most inspiring war film remains Philippe de Broca’s (1933 – 2004) King of Hearts = Le Roi de cœur (1966). The film is set in a set in a small French town towards the end of World War I. Retreating Germans have placed a bomb in the town square, and it is up to signaller/ pigeon keeper Charles Plumpkit to defuse the bomb. While normal residents flee, inmates from an asylum take over the town, and challenge conventional values. The film also questions the very notion of sanity.

A confession: I have never served in any military, and describe myself as a pacifist. In my youth, I have known people who have served in the sea cadets, based at the New Westminster Armory. Many of them were musicians. In Norway, I have worked with teachers who choose to leave the school system temporarily, to work as soldiers in peace-keeping missions, most often in the Middle East. I have never understood the appeal of being in the military.

Note: the next weblog post is scheduled for Tuesday, 2023-10-31.

Thank you for these words Brock, I found them disturbing and also comforting in there is at least one other person with similar views to myself.

Thanks also for the intro to Baha’i.

A pleasure, Peter. It is also reassuring to know that there are like minded people living in Norway.