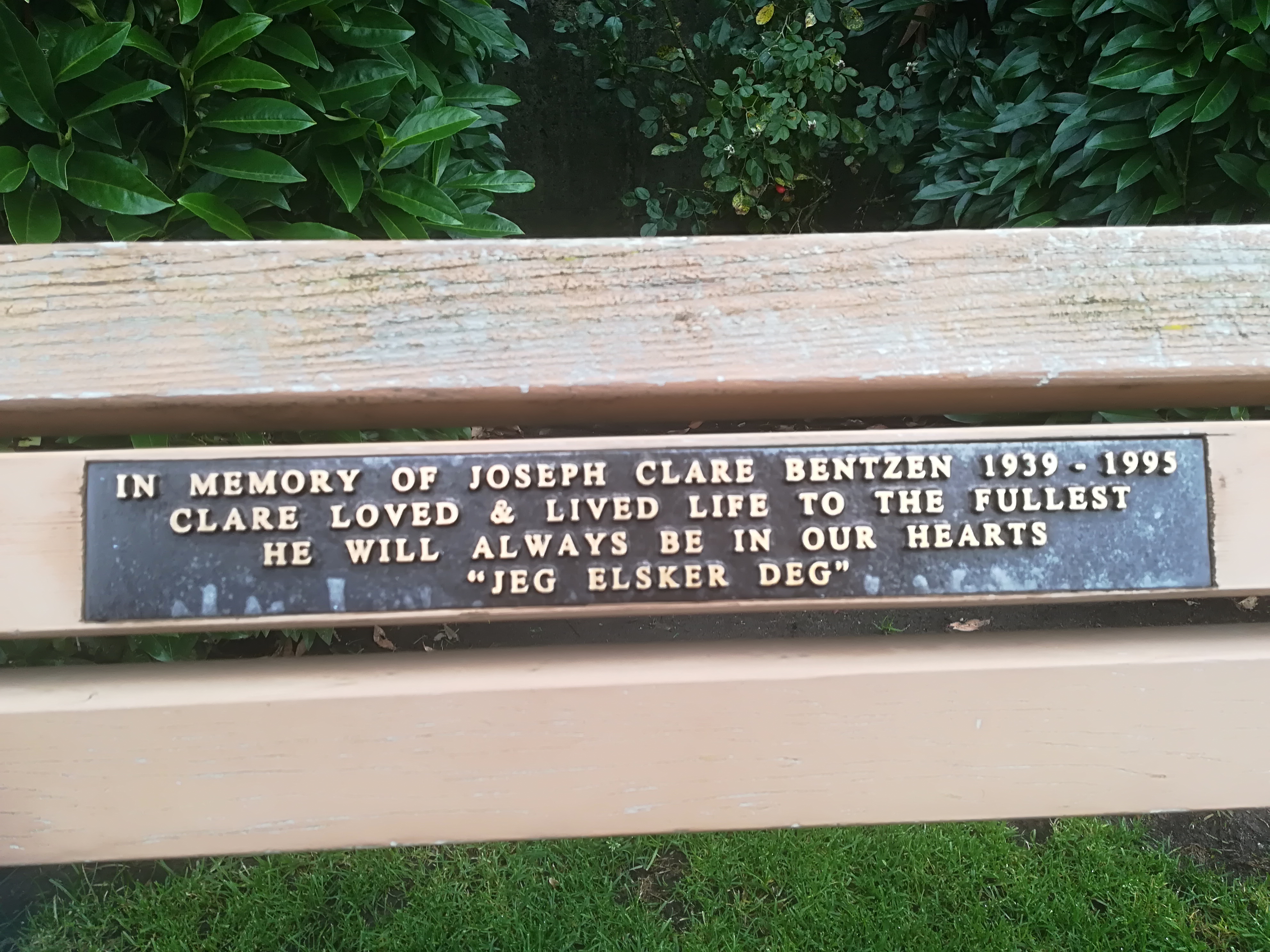

Fictional worlds are real. They frequently exist in the minds of authors and artists, not to mention those of their readers and viewers. Unit One is, at best, only half fictional. It consists of a tangible workspace, currently under construction, at Vangshylla, Norway, as well as a co-located, intangible faux-institution, Ginnunga Gap Polytechnic.

While Trish & Brock McLellan are real, personas Daffy & Jade Marmot are fictional. Marmot family members, and other personas, can express alternative (even contradictory) values to those of living people. That’s one reason personas are fun people to be with.

Most first class polytechnics as institutions have had their names changed. In Britain, most lasted only from 1965 to 1992. Almost all have become second class universities. Whereas polytechnics were grounded in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) and teaching oriented towards professional qualifications, the new universities offer a wider variety of courses, frequently in the humanities.

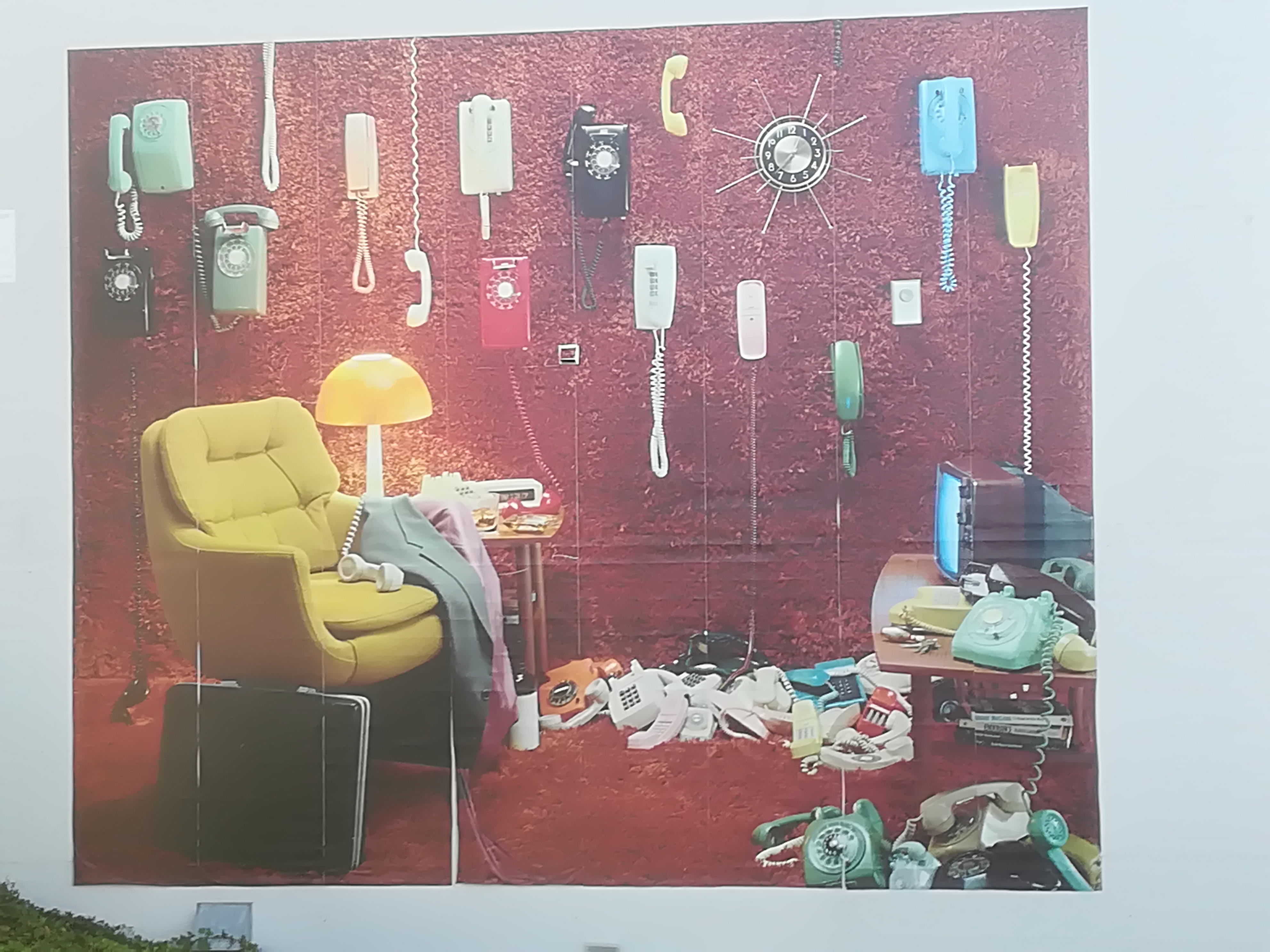

The purpose of Unit One, both the workspace as well as the faux-institution, is not to make stuff. It is to promote “Innovation & Equality – for a better world”. The term workspace is used instead of workshop, because workshop has lost much of its original meaning: “A room or building in which goods are manufactured or repaired” as it acquired an additional meaning: “A meeting at which a group of people engage in intensive discussion and activity on a particular subject or project.” (Oxford Dictionary)

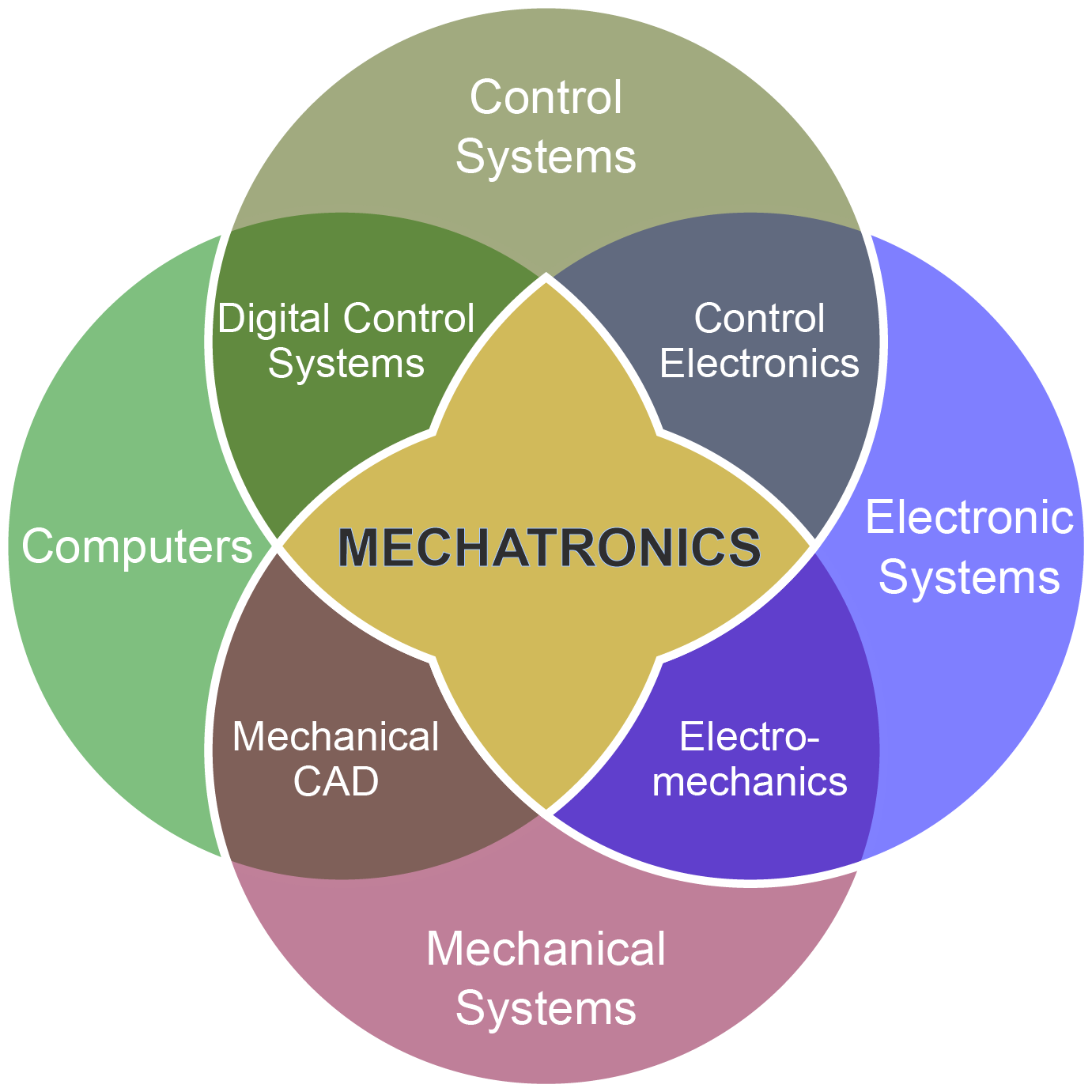

From the beginning of the new year 2018, the Unit One workspace will be a place to develop (as in innovate), build and use equipment. The space and machine park will be available for others to use, under some conditions, but free of charge. The space and equipment will also be available for the sharing of knowledge and skills in woodwork and metalwork, microprocessors, mechatronics, robotics and the like. Target users include disadvantaged groups, especially women, young people and immigrants.

The Garden Project will show some of the thinking at Unit One. One consequence of constructing the Unit One workspace, was the displacement of the gardener from her shed. It became the Unit One Annex. Thus, one of the first products to be built at the Unit One workspace, will be a replacement shed, built on SIP (structural insulated panel) principles, which can be used for storage of equipment and more. In addition, a geodesic dome will be built that can be used as a greenhouse.

Unit One is scheduled to open on Monday, 01 January 2018 at 12.00 noon. At the moment a number of speakers have been invited to entertain guests.

1. Proton Bletchley: Unit 1 – A community work space? (10 minutes)

2. Precious Dollar: What does it cost to build a workshop? (10 minutes)

3. Billi Sodd: Workshops in Prison (This is dependent on Billi being given day release from Verdal prison) (unknown duration)

4. Refreshments

5. Jade Marmot: The fun with DIY videos (30 minutes)

6. Brock McLellan: Concluding remarks (10 minutes)

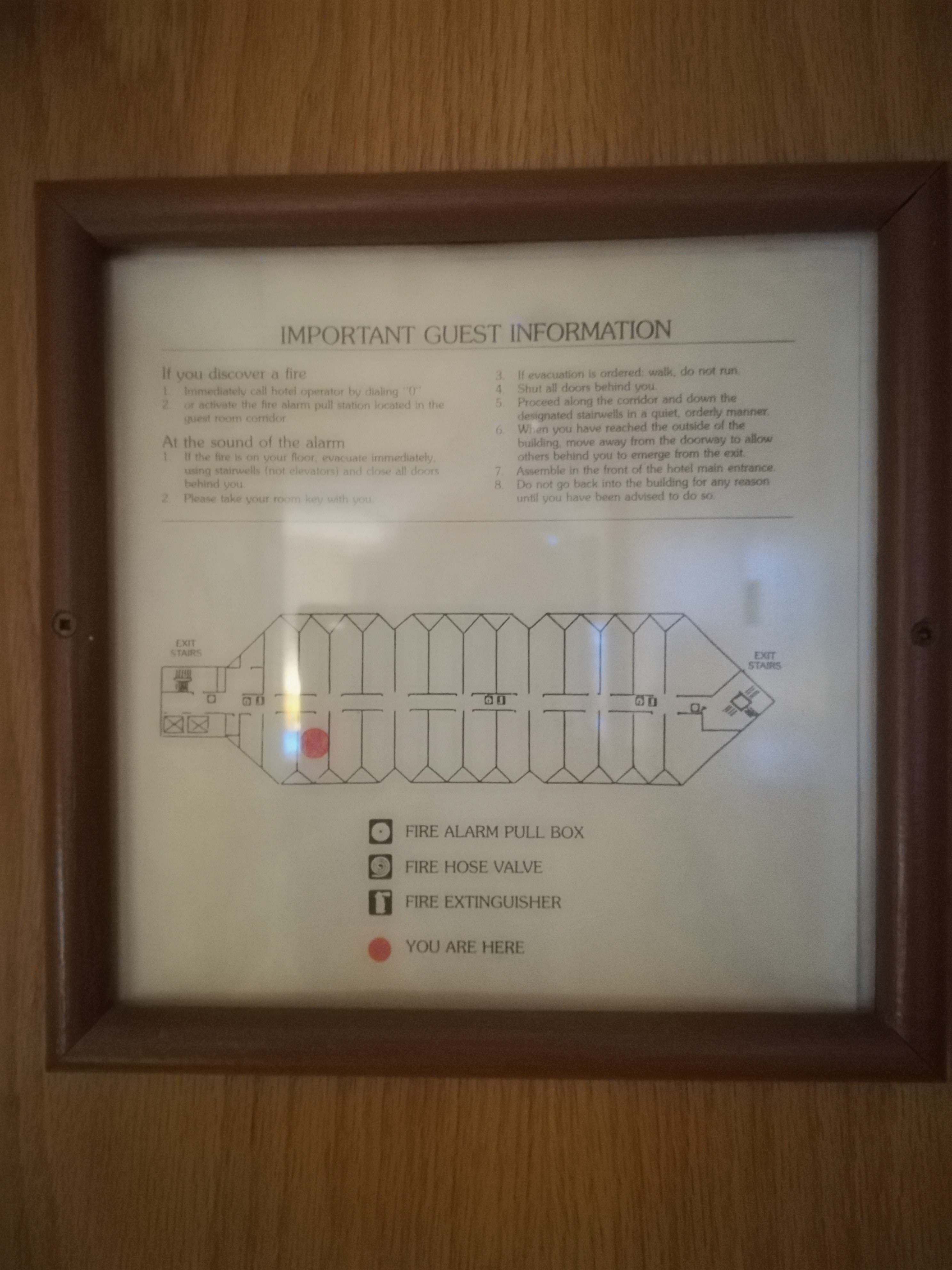

After the official opening, at 14.00, Ginnunga Gap Polytechnic’s first course will be offered. It is a 2-hour health, environment and safety course for people who want to use the workspace. They will receive training on how to protect themselves from danger, when working in the workspace.

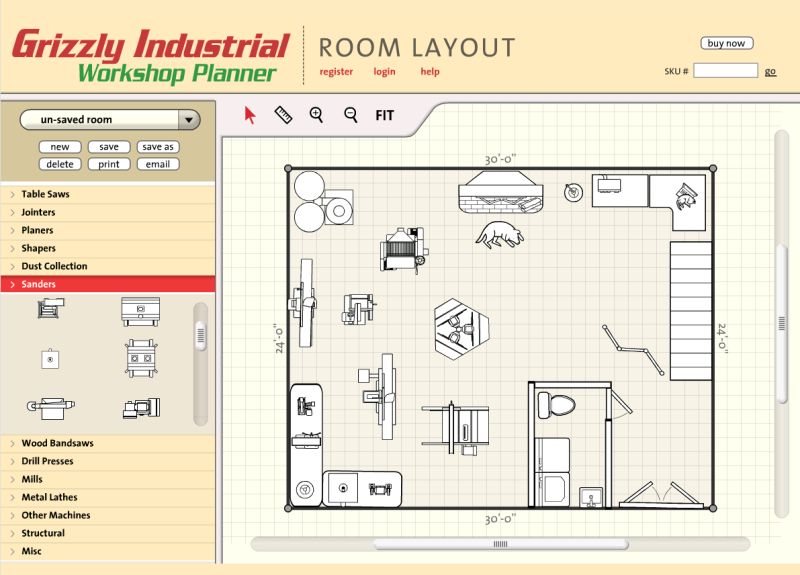

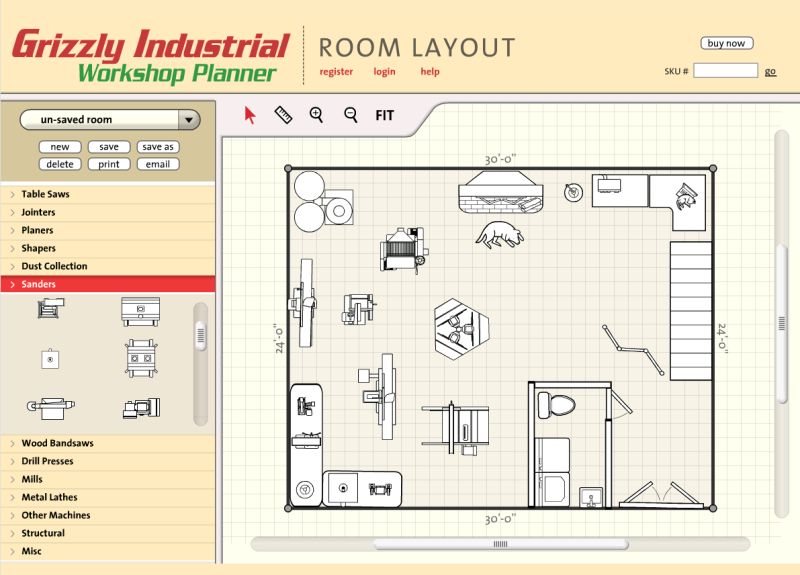

Initially, the equipment at the workspace will focus on woodworking. A number of stationary machines will be available, if not on the opening day, soon after: table saw, band saw, miter saw, router, planer, jointer and drill stand.

As time progresses new equipment and courses will be added. In fact, it may be desirable for other people to build and share new workshops. In other words, a Unit Two, Unit Three … It will be up to other people to decide.

Despite this suggestion, Unit Two may not be something physical at all, but another fictional environment, a virtual work space, with a focus on creating instructive videos that can be viewed by anyone anywhere. This is the type of topic to be discussed at a monthly “fredags fika” (Friday Coffee). This will be a forum for people to discuss how they want to use the workspace, its development over time, and rules needed for its use.