A large portion of a person’s identity is related to geography. This weblog post explores some issues related to identity, from a very personal perspective.

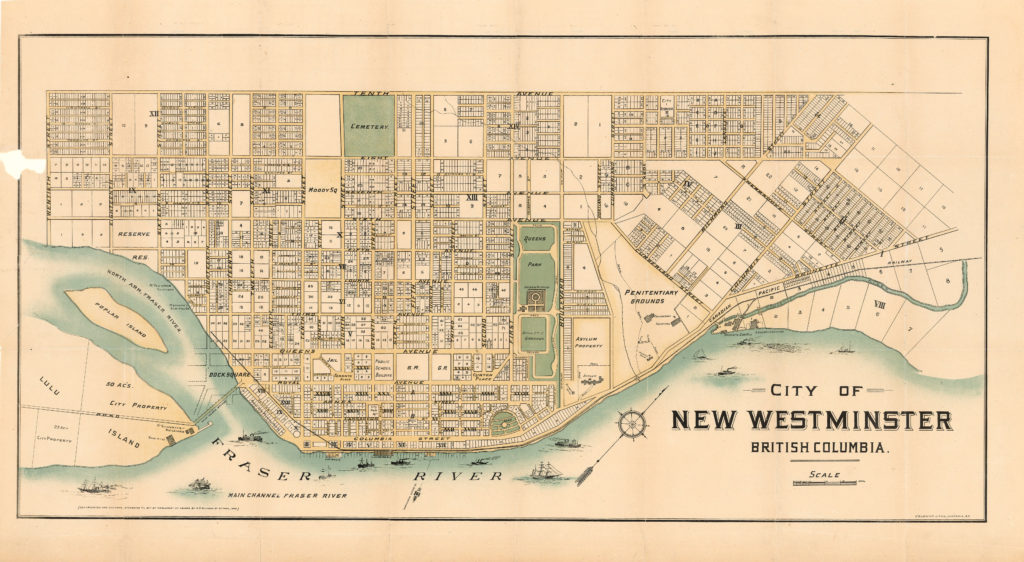

The above map of New Westminster, is oriented as its citizens conceive of their city, with the west on the left and the east to the right, with the north at the top, and the south at the bottom. Streets run south to north, avenues from east to west. Even numbered addresses are on the southern and western sides, odd numbered on the northern and eastern sides. Unfortunately, even these basic facts aren’t actually true. The compass near the bottom of the map helps explain it. The streets run from the south-east to the north-west. The avenues from the north-east to the south-west.

For over forty years I have been an immigrant to Norway, and probably will have that status for as long as I live, despite acquiring Norwegian citizenship 2021-05-07. Even my children cannot escape that term, despite both of them having been born in Norway. They are regarded as second-generation immigrants. Sometimes, they are referred to as third-culture children. It means that they are not fully integrated into the country/ culture of their citizenship, in our case, British Columbia/ Canada, nor that of their birth, in our case, Norway. It is a common situation.

I grew up in New Westminster, British Columbia. It was founded by the Royal Engineers, led by Colonel Richard Moody (1813 – 1887), to be the capital of the Colony of British Columbia in 1858, and continued in that role until the colony’s merger with the Colony of Vancouver Island in 1866. New Westminster was the largest city on the mainland, from that year until it was passed in population by Vancouver during the first decade of the 20th century.

The most prominent street on the map of New Westminster is fifth street, where my sister lives. The architecture is attractive. Some patriots might even call it majestic with traffic divided by a boulevard. This was to be lined with foreign embassies, but by 1871, when British Columbia entered Canada, this dream came to an end. Victoria had become the capital of the united colonies. I know too much about New Westminster’s history, especially its racism, to want to live there again.

My biological/ ethnic/ cultural identity has emerged, and become more complex, with the years. I have always known that I was adopted, that I came from a family of farmers, and that my biological father had served in the Royal Canadian Navy, during World War II. I was given my original birth certificate with my original name, by my father, some months before he died in 1991. Here it stated my original name, Richard Edwin Salter. I received information about my biological mother in 2006, and even met some of her family in 2007, more of them in 2008. For the first time in my life, I could see people who had some of my physical characteristics, blue eyes and large hands, especially. I even had a place of origin, Essex County, Ontario, but with English origins from Cornwall and Irish origins from Greyabbey, with ancestors that had started off in the Orkney Islands, with roots pointing to Norway.

In 2015, gene testing through 23 & Me provided me with even more revelations, including some First Nation genes. Just before I turned 70, my biological half-brother contacted me. While he was born in Windsor, Ontario, his family had moved across the river to Detroit. My paternity can be traced back to Fredrikstad in Norway, and from there to New Amsterdam and Schenectady, New York. I have Dutch and French genes as well. The First Nations genes turn out to be Mohawk.

I too feel as if I am a third-culture child. I have never been fully integrated into my adoptive mother’s family, nor can I ever fully integrate myself into my biological family. I also lack the mindset to be a fully integrated Norwegian.

My mind inhabits Qayqayt, the co-located First Nation village, usurped by New Westminster. It also inhabits New Westminster, Inderøy, Essex County and Detroit. Somehow, I manage to live in all these places simultaneously. Such is the power of the mind, and emotions.

When I visit Qayqayt/ New Westminster, every block resonates with memories. The remaining half of my old neighbourhood is protected from development, including my childhood home, hopefully none of these houses will come crashing down during the remainder of my life. The other half was destroyed in a housing boom in the 1970s, when single family dwellings were replaced with three-story, wooden apartment buildings.

Using thesaurus.com, to find synonyms for migrant, there appear to be different classes that meet their definition of “a person who moves to a foreign place.” Emigrant and immigrant are the most neutral terms that focus on leaving or entering (a country), respectively. I have not come across migrator or departer before, and mover does not imply anything foreign. Expatriate may also express some of the same sentiments, but it is a term I refuse to use. While evacuee appears on the list, refugee does not. Drifter, itinerant, nomad, rover, transient and wanderer all express a more temporary relocation, even if it is one that is part of a lifestyle, imposed or chosen. Vagrant seems almost criminal, while gypsy, tinker and traveller reflect ethnic orientations.

Migration is magnetic. There are some forces that push a person away from their home country, but other forces that pull them to a new destination. For some, money is a very compelling force. For others, it barely enters the equation. Personal safety may be a concern for many.

Of the various places I have known and visited, I am content with Inderøy. It is sufficiently hilly, and close to the sea to satisfy these primal needs. Qayqayt was on Sto:lo, that is, New Westminster was on the Fraser river. Essex County and Detroit border on the Detroit River. I can mentally relate to them by relating them to the Fraser Valley, and its farms.

I am uncertain if I could move to Essex County. I find the town of Essex attractive, but a little too flat. If something forced a relocation from Inderøy, I am most attracted to the landscape surrounding the Salish Sea. Ninety percent of it, is encompassed on the route from the Malahat on the south-eastern shore of Vancouver Island, northwards to Courteney, then across to Powell River, and further south to the Sechelt peninsula.

I may live in Norway, but almost all of the recent books I have purchased are about British Columbia, typically on or near the Salish sea.

Much of the early history of British Columbia was researched, written and published by Hubert Howe Bancroft (1832 – 1918), born in Granville, Ohio, but who moved to San Francisco in 1852 where he started the largest bookseller, stationer and publishing house west of Chicago. He started researching the history of British Columbia on a trip to Victoria in 1878, and came out with a definitive history of the province in 1887, written by himself, William Nemos (Swedish), Alfred Bates (English) and Amos Bowman (1839 – 1894), from Blair, Ontario. The major challenge with this work is its emphasis on pioneer history, where settlers of European origin set the premises for the work. It is the migrants to the area that are intent on determining its history. Despite the First Nations populations far outnumbering these settlers, they were largely ignored, as were people of Asian origin. Bancroft did, however, manage to strike a balance between British and American perspectives on the province.

The next significant historian was Frederic Howay (1867 – 1943) born in London, Ontario, but who moved first to the Cariboo goldfields in 1871, and then to New Westminster in 1874. He studied law at Dalhousie University, graduating in 1890. He was appointed a judge in 1907, retiring in 1937. He used as much of his working day as possible writing history.

For years, I have coded it as NW, until today. News of the tragedy at the Kamloops Residential School, has prompted me to refer to the city from now on, as Qayqayt, or Qt. I lived at the residential school in Port Alberni on Vancouver Island, during the summer of 1974, as an archaeology student working on a nearby excavation.

Despite years of effort by my mother, who grew up in Kelowna, although she was born in Vancouver (Eburne is the name appearing on her birth certificate). I never felt at home in the interior of British Columbia, as an adult. The one exception was Madeira, a cabin at Blind Bay on Shuswap Lake. For me, civilization ended at Hope. Almost everything beyond felt like the frontier. Since the early 1970s, whenever I think of the interior, I think of Robert Altman’s (1925 – 2006) film, McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971), based on a 1959 novel of the same name by Edmund Naughton (1926–2013), and set in a 1902 Bearpaw in Washington state. That is despite the rain, the vegetation, and most of the film being shot on location in West Vancouver and in Squamish,

Before opening his own butcher shop in Kelowna, my maternal grandfather was a cattle buyer. He rode a horse, and was armed.

Before moving to Norway, we applied then met with the consul in person in Vancouver. He admitted that he wanted to make sure that we were of the correct race. During our meeting he received a telephone call. From his remarks, it was obvious that the person calling was the widow of a Norwegian citizen who had immigrated to Canada. After he died, she discovered that he had another wife, children and family in Norway that she had not heard about previously. His bigamy was making her life difficult.

There are times when I regard myself as a third-culture child.

Despite having lived in Norway for over 40 years, people can hear my foreign origins. While some ask if I am American, others have been more complimentary asking if I was from Finland or even Denmark.

An aside on orthography. At elementary school I had difficulty spelling, as well as with the art of handwriting/ penmanship/ penpersonship. I am aware that tradition dictates that fifth street should be written Fifth Street. I prefer not to write it that way any more, as a Norwegian writing style seems more natural. Similarly, while others may encourage me to write the Fraser River, I often write Fraser river, but would prefer to write Sto:lo which is its name in the Halqemeylem (Upriver Halkomelem) language.

This preference has been reinforced following the discovery of the remains of 215 children at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, and the subsequent discovery of even more, at other schools. I can no longer accept the use of names imposed by English invaders on the landscape they referred to as British Columbia. #EveryChildMatters.

The first Richard McBride Elementary School, in the Sapperton neighbourhood of New Westminster, was built in 1912. It burned down, and was replaced by a second school in 1929. Now, that school is being replaced. In the Brow of the Hill neighbourhood, John Robson elementary school, has been bulldozed away and replaced by École Quaquat Elementary School, offering dual track French and English immersion programs. Richard McBride urged the Canadian Prime Minister to support legislation banning immigration from Asia. He dispossessed Indigenous people of reserve land, and opposed women’s suffrage.

The New Westminster school district has launched a renaming process for the school after a request from McBride’s parent advisory council (PAC). At issue are the opinions and actions of Richard McBride, the 16th premier of British Columbia, from 1903 to 1915. He held publicly expressed views against Asian and Indigenous people and against women’s suffrage. Throughout his time in office he oversaw legislation reflecting those views.

New Westminster school board has pledged its commitment to undertaking anti-racism work in the district. The naming proposal came from PAC secretary, Cheryl Sluis, and was discussed at the group’s annual general meeting in 2020-06, held virtually due to COVID-19.

New Westminster has become a diverse city. There is a need for children to identify positively with the name of their school, and for the name to reflect values of equity and inclusion. Despite this the renaming proposal has its critics. Allegedly, some people don’t want (racist) history erased and want to honour New Westminster’s Anglocentric traditions. My attitude towards New Westminster stems from being denied an opportunity to participate at the May Day dances, performed by third grade classes. I was one of two people excluded, probably because of my cerebral palsy.

The school district is now fully in charge of the renaming process. School district superintendent Karim Hachlaf wrote in a letter dated 2020-06-24 to the McBride PAC that an operations committee will be established that will include a wide range of staff and community representatives: a trustee, administrative staff, union representatives from both CUPE and the New Westminster Teachers’ Union, community members, student advisory members, a PAC representative and possibly more. Once the list of participants has been finalized, the committee will meet to recommend a plan and consultation timeline to the board. After it carries out its consultation process, the committee will present a summary report and recommendation to the board, and the school board will make the ultimate decision about a new school name. [Note, the school is now officially known as Skwo:wech Elementary School, discussed in the post, Homebound.]

This reply was prompted by a 2020-06-22 letter to the New Westminster school district, from the Richard McBride Elementary School PAC executive outlined some of their findings:

During his time as premier (1903 to 1915), McBride advocated for “a white B.C.” and sought to shut out the “Asiatic hordes.” He worked hard to prevent “cheap” Japanese labour from competing in the fisheries and in “everything the white man has been used to call his own.”

McBride led the legislature in passing numerous anti-Asian measures, such as taxes on companies that hired Chinese labourers and legislation denying the vote to Asians and Indigenous people.

After the Conservatives formed the federal government in 1911, McBride urged Prime Minister Robert Borden to honour a promise to legislate against immigration from Asia.

McBride was premier at the time of the Komagata Maru incident, when the Japanese steamship carrying hundreds of Sikh passengers was prevented from docking and most of its passengers were barred from entering B.C. McBride was quoted as saying: “To admit Orientals in large numbers would mean the end, the extinction of the white people.”

As premier, McBride pursued a policy of making way for economic development and the expansion of cities by dispossessing Indigenous nations of their reserve lands.

McBride was also well-known as a leading anti-suffrage politician at a time when white women were gaining the vote across Canada. He believed extending the franchise to women would take away too much power from men.

Other identities

As an adopted person, I also have a number of adopted identities, that I refer to as personas. [These were discussed in a very early post from 2016-05-12, Unit One.]

Note: This was originally planned to be published in 2021, somehow it wasn’t. Parts of it were published in Homebound, mentioned above, published 2022-04-23. Then accidentally, this post was published on 2022-10-27, despite a publication date of 2021-12-05. Please excuse the repetition of information.