This is the third consecutive year that a weblog post has been published for World Goth Day, potentially celebrated by tens of people, throughout the world! This year it arrives one day early 2022-05-21, with a focus on fashion. The two other weblog posts were: World Goth Day #12 which looked at some of the origins of the day, and #13 with a focus on music. Future efforts: #15 is planned to look at Gothic architecture from the mid-12th century to the 16th century; #16 will look at the historic origins of the Goths in Scandinavia and their dispersal southwords; #17 will examine will look at their relationship with Rome.

Goths as outsiders

More than seventy years of living, and years as a teacher, has taught me that people do not choose to become outsiders. Rather, social forces – outside of their control – largely determine it. They become victims, and the victim is left to deal with the consequences of their victimhood. One way of coping with their situation, is for these victims to visibly display their outsider status. This display takes many forms, but one prominent way is in terms of clothing.

A fashion statement cannot be made alone, it takes place inside a context. That context may be temporal, geographical or cultural, but often involves all three elements.

A. Insider

Haute Couture

Charles Fredrick Worth (1825 – 1895), from Bourne, Lincolnshire, England and his partner Otto Gustaf Bobergh (1821 – 1882), from Bernshammars bruk, Västmanlands county, Sweden, established Worth & Bobergh, in Paris, in 1858. This company is regarded as the first haute couture establishment, with Worth the first fashion designer, and Bobergh the business manager. Some of its innovations included transforming the salon into a meeting point when clients came for consultations and fittings; advanced client selection of colors, fabrics, and other details; replacement of fashion dolls with live models; sewing branded labels into clothes. By the end of Worth’s career, Worth & Bobergh employed 1 200 people and its impact on fashion taste was far-reaching.

Haute couture has a legally protected status, defined by the Chambre de commerce et d’industrie de Paris, an organization started in 1868. Rigorous rules were implemented in 1945, which required: made-to-order design for private clients, including at least one fitting; a workshop (atelier) located in Paris, employing at least fifteen full-time staff members; at least twenty full-time technical people, in at least one workshop (atelier); and the presentation of a collection of at least 50 original designs to the public in January and July of each year, with both day and evening garments.

For those wanting to read more, Wikipedia provides an extensive number of links to both existing and former haute couture fashion houses: Balenciaga, Callot Soeurs, Pierre Cardin, Chanel, André Courrèges, Christian Dior, Mariano Fortuny, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Christian Lacroix, Jeanne Lanvin, Ted Lapidus, Mainbocher, Hanae Mori, Thierry Mugler, Patou, Paul Poiret, Yves Saint Laurent, Maison Schiaparelli, Emanuel Ungaro and Madeleine Vionnet.

Traditional Crafts

Being an insider is not synonymous with being urban and rich. Sometimes, it can be associated with traditional values in a rural environment. In Norway, the first handicraft schools were established in 1870, becoming mechanisms for promoting Norwegian cultural values.

The Norwegian crafts association = Norges Husflidslag, was founded in 1910. Its purpose was, and still is, to strengthen Norwegian crafts. In 2017, the organization had 24,000 members, 360 local groups, 36 shops that are wholly or partly owned by county/ local groups. It is a member of the Norwegian Cultural Conservation Association. In 2014, the organization was accredited by UNESCO as the third Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) with expertise in intangible cultural heritage. As a member of the Study Association for Culture and Tradition, it joins other organizations that work with popular cultural expressions, including folk dance, theater, cultural heritage (including the preservation of the maritime environment) and local history.

After the end of World War II, crafts (and schools to teach them) came into focus as a means of increasing women’s contribution to farm income. The Ministry of Agriculture appointed a committee in 1946 to look more closely at craft training. This resulted in a proposal, to establish (mostly) publicly run handicraft schools in all counties. Courses were adapted to the needs and interests of young women, especially, and the schools offered both half-year and full-year programs of study. In 1955, the handicraft schools were transferred from the Ministry of Agriculture to the Ministry of Church and Education. In 1966, the Oslo Industrial School for Women = Den Kvindelige Industriskole i Kristiania, established in 1875, became a vocational teacher’s college, and changed its name to the State Teaching College for Crafts = Statens lærerskole i forming . Two other colleges for crafts were also established. These were essential for recruiting teachers for the handicraft schools.

By 1976, the teaching of handicrafts and aesthetics was now incorporated into the upper secondary school system. An introductory course with a focus on drawing, and aesthetics more generally, formed the basis for advanced courses in weaving, sewing and wood and metalworking. A third year course trained people to become activity therapists. While students used to be older, the schools gradually adapted to teaching younger people, most between 16 and 19 years of age.

Starting on 1980-08-20, Patricia, my wife, studied one year of weaving followed by one year of sewing, at such a school in Molde, while I took a half year introductory course, starting in 1981-01 followed by a year of wood and metal working. At the same time, we learned Norwegian. The school had 120 students, some in their late teens, many in their early twenties, but with some older people. I was one of two male students at the school. Attending this school gave me insights into traditional Norwegian cultural values, but also labeled me as an outsider.

This was not my first excursion into textiles, in 1978 Patricia and I both took a spinning course at the Deer Lake Art Centre, in Burnaby, adjacent to New Westminster, British Columbia. Later, I purchased one of the first electric spinning wheels made by Kevin Hansen on a visit to Port Townsend, Washington. Apart from a few minutes of experimentation, it remains unused.

Modesty

To gain insights into modest fashions, I started to read Hafsa Lodi (ca. 1988 – ), Modesty: A Fashion Paradox (2020), further described as a work that uncovers the causes, controversies and key players behind the global trend to conceal rather than reveal. Despite my attempt to suspend disbelief, as Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834) advised, and to read the work as the author intended, I found it difficult to understand the author’s perspective.

Her primary consideration is that garments conceal, although the extent of concealment varies. The minimal amount varies “by culture, class, ethnicity and generation” (p. 17) but usually means that the garment(s) cover the knees and shoulders. Some want to extend these to covering ankles, elbows to wrists. So far, so good.

However, the fashion she was advocating was not modest in my interpretation of the word, which would include characteristics such as sustainable, durable, comfortable and moderately priced. Instead, the garments she promotes are prized for their designer label and extravagance. She even uses the term luxury modest wear. They may have concealed some skin, but revealed a pretentious origin in haute couture.

Within her world, these garments may be modest. Dubai, and other countries in the Middle East, have the least economic equality of anywhere in the world. Thus, there are some people who can enjoy a luxurious life, because they subject others to a life of servitude and drudgery. It is also the area of the world where patriarchy excels.

Admittedly, having matured in the 1960s, my sense of modesty is tempered by that eras fashion trends. There are modest, and not so modest, mini-garments. In the debate about the inventor of the miniskirt, I am inclined to accept the judgement of Marit Allen (1941 – 2007), half-Norwegian fashion journalist and costume designer, who credits John Bates = Jean Varon (1938 – ) with its conception, and execution in 1965 in outfits for Diana Rigg (1938 – 2020) for her role as Emma Peel in The Avengers. His work included not just skirts and dresses, but Op-Art mini-coats. I have discussed Rigg and Bates in a previous weblog post. I find most of these garments modest! Both André Courrèges (1923 – 2016) and Mary Quant (1930 – ) have been designated the inventor of the miniskirt, by others. I will acknowledge Courrèges role in promoting/ introducing jeans for women.

While there is an attempt to create a gender divide, especially with respect to the use of trousers, there has been fluidity in the use of garments throughout the millennia. An introduction to insights into this topic, can be found in one Wikipedia article on Trousers as Women’s Clothing. Divided skirts were used in the late-nineteenth century for horse- and bicycle-riding. These were rebranded as culottes in the mid-20th century. These have increasingly replaced skirts in many situations. One of the first being that skirts worn by female medical personnel were incompatible with the wake produced by helicopters.

B. Outsider

In Fear and Clothing: Unbuckling American Style (2015), Cintra Wilson (1967 – ) advises: Your closet is a laboratory in which you may invent astonishingly powerful voodoo. It may be used as a tool to direct yourself toward your own ideal destiny. It’s geomancy—portable feng-shui, right on your body. Style is one of the most remarkably fast, proactive, and gratifying ways to change your mind, change your mood and—as a surprising result—change your circumstances. It is one of the most direct ways of exploiting the Socratic adage “Be as you wish to seem,” or, more slangily, “Fake it till you Make it.”

Most outsiders lack the resources to purchase bespoke/ haute couture clothing, or to make their own traditional clothing. Many are a product of a cycle of poverty, forcing them into unskilled jobs at an early age. Many have also suffered various types of abuse, making participation at school or in the labour market difficult.

Lingerie

In 1913, Yva Richard, transformed himself from Paris photographer, to the proprietor of a lingerie boutique, run either by himself or, more likely, his wife Nativa Richard. Their unique creations became increasingly daring/ avant-garde/ erotic, and by the late 1920s, they had develop a successful international mail-order business, based on a catalogue of photographs taken by Yva, frequently modelled by Nativa. It lasted until 1939. Léon Vidal, a tailor and owner a chain of erotic bookshops, was encouraged by the success of Yva Richards, to open a competing boutique, Diana Slip. It, too, lasted until the start of World War 2. Numerous not safe for work (NSFW) and some more socially acceptable photographs of their creations can be found using a search engine.

Vampire

If there is one element that unites the young goths that I have met at secondary schools and in prison, it is their fascination with vampires. The vamp(ire) has become a symbol of an extreme outsider. The first poems with a vampire in English, was Robert Southey’s (1774 – 1443), Thalaba the Destroyer (1801). This was followed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834), Christabel (written 1797 – 1801, published 1816). There are shorter references to this theme in George Gordon Byron (1788 – 1824) in The Giaour (1813). The first modern vampire prose work in English was John William Polidori’s (1795 – 1821), The Vampyre (1819). At this point, the representation of vampires in literature explodes.

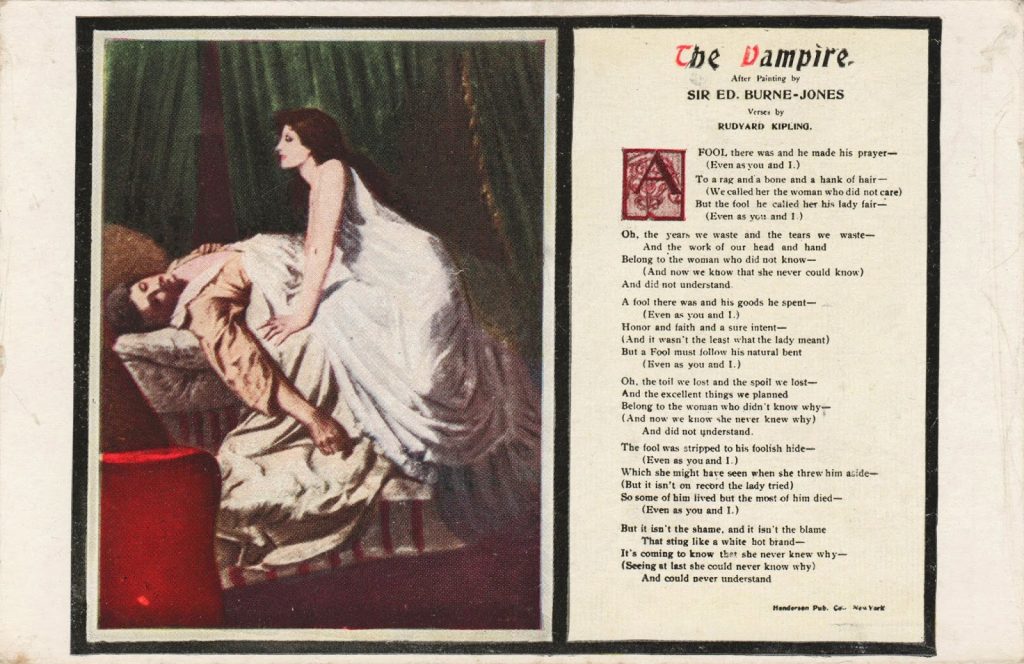

The height of vampiremania is reached in 1897. Philip Burne-Jones’s (1861 – 1926) paints, The Vampire (1897). This inspires Rudyard Kipling’s (1865 – 1936) to write his poem, The Vampire (1897). Then Bram Stoker’s (1847 – 1912) Dracula (1897) appears, and the world has never been the same again.

Fast forward to the present and vampires are still with us. On Goodreads, I encountered a list with 1 669 (at the time of writing) best vampire books! At the top of the list is Stephen King’s (1947 – ) second published novel, Salem’s Lot (1975). This work is expected to reappear soon as a film with the same name, directed by Gary Dauberman (ca. 1977 – ). Of course, there are numerous other films and television series that have vampires as an essential plot element.

Black

As a sign of their outsider status, people often opt to dress provocatively. Karl Spracklen and Beverley Spracklen, The Evolution of Goth Culture: The Origins and Deeds of the New Goths (2018) describe this provocation, and fundamental characteristic of Goth fashions in one word – black (Chapter 11: Goth as Fashion Choice). Many of the Goths I met teaching were consumers of Gothic Beauty, from 2000, and/ or Dark Beauty Fashion Magazine, which appeared from about 2010 to 2020. These offered a slightly broader colour pallet.

According to Cintra Wilson in an article You just can’t kill it (2008), this blackness has its origins in the Victorian cult of mourning. Thus Steampunk and related fashions with origins from this time period are embodied into the dress code.

Beyond this darkness there was a fascination with hair, typically dyed. The mohawk represents one of the most admired, if less frequently used, hair styles. It involves a narrow, central strip of upright hair running from the forehead to the nape, with the sides of the head bald. Variations include: the nohawk, a shaved strip from the forehead to the nape of the neck, with hair on either side of that strip; the Eurohawk, where the sides are not shaved, but with shorter hair than on the central strip; and, the fauxhawk, a hairpiece in the form of a mohawk.

Boots

Yet, as a sign of their outsider status, some people often opt to dress protectively. Perhaps, the best display of this is characterized by Doc Martens boots, made at Wollaston in Northamptonshire, England. These boots originated with Klaus Märtens, a doctor in the German army who had injured his ankle towards the end of World War II. Standard-issue army boots were too uncomfortable, so he designed improved boots, using soft leather and air-padded soles made from tires. In partnership with Herbert Funckt in 1947, footwear based on these improvements were made at a German factory, and sold primarily (80%) to older (40+) women. In 1959, British shoe manufacturer R. Griggs Group bought patent rights to manufacture the shoes in Britain. Here they the name to Dr. Martens, slightly re-shaped the heel, added yellow stitching, and trademarked the soles as AirWair. It took until the late 1970s for the brand to become synonymous with youth subcultures, including Goths.

Sewing

In a house filled with books, my estimate is that about 100 of them are related to textiles, in some form or other. Topics include: spinning, weaving, fashion design, pattern making, sewing, knitting and other forms of manipulating yarn. Then there are binders and boxes filled with patterns. Some of these works are older than the residents in the house. One was purchased a week before this comment was written.

I have tried to go through these to find one suitable book that will provide sufficient insight for beginners to learn to sew clothing. This book is by Alison Smith, The Sewing Book: Over 300 Step-By-Step Techniques (2018). It costs about US$ 21 in hardback. This can be followed by her Sew Your Own Wardrobe (2021). It costs about US$30 in hardback. Once basic skills are developed, additional insights can be developed, for example, using Claire Shaeffer, Couture Sewing Techniques (revised edition, 2011). It is about 250 pages in length, shows the history of couture fashion, and is available in both paperback and digital versions for about US$ 17. All prices are at the time of writing.

An electric sewing machine is a necessity for any normal person wanting to make garments. There is no need to purchase the most expensive models. They offer a lot of features that will probably go unused. The most important characteristic is that it has capabilities for making button holes. Our household has a Janome Decor Computer 3050, which costs about US$ 700.

Goth Day

This weblog post was published on 2021-05-21, one day prior to World Goth Day #14.

Så artig at du har dykka dypt med i søm og historie rundt det. Til og med mote har du med. Ønsket mitt om å sy min egen garderobe har vært med meg hele mitt voksne liv. Kanskje når jeg blir pensjonist vil jeg få mulighet til å prioritere det. Da gjerne med gjenbruk av stoffer og omsøm av gamle “klenodier” som henger i skapet. 😊

Well done, Brock!

English translation from Google, with a little help from Brock

So fun that you have dived deep into sewing and the history around it. You have even included fashion in it. The desire to sew my own wardrobe has been with me all my adult life. Maybe when I retire I will have the opportunity to prioritize it. Then preferably reusing material and sewing old “treasures” that hang in the closet. 😊

Well done, Brock!