The reason for writing this weblog post is not because of this webloger’s competence in psychology, which is – at best – elementary. Rather, it comes from an attempt to understand music therapy as an approach to relieving depression. It seems to help some people, but not others. Another challenge is to find out why some people find one type of music pleasurable, while something kindred does not produce this type of response, in the same person!

Foreground

French psychologist Théodule-Armand Ribot (1839 – 1916) introduced the term anhedonia in 1896. Prior to this, symptoms were described in 1809 by the English physician John Haslam (1764–1844). Some describe anhedonia as a reduced ability to experience pleasure. Others refer to it as an (emotional) numbing of a reward. Some researchers suggest that anhedonia may result from the breakdown in the brain’s reward system, involving dopamine. They characterize anhedonia as an impaired ability to pursue, experience and/or learn about pleasure. About 70% of people with a diagnosis for depression show signs of anhedonia.

Many researchers distinguish between wanting and liking something. In wanting, it is the anticipation of something such as food/ sex/ music that provides a reward. In liking, it is the consumption of that reward that is pleasurable. These may have biological/ pathological considerations.

Anhedonia is common in people who are dependent on drugs, including alcohol, opioids and nicotine. While anhedonia becomes less severe over time, it is a significant predictor of relapse. People with Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease show increased levels of anhedonia. Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) patients and schizophrenics display symptoms that correlate strongly with the wanting aspects of anhedonia.

At this point, it could be helpful to distinguish between auditory agnosia, amusica, melophobia and musical anhedonia.

Auditory agnosia is inability to recognize or differentiate between sounds. It is not an ear or hearing defect, but a neurological inability to process sound meaning.

Amusia is a musical disorder that appears mainly as a defect in processing pitch but also encompasses musical memory and recognition. Two main classifications of amusia exist: acquired amusia, a result of brain damage, and congenital amusia, a music-processing deficiency present since birth. Some people with amusia, lose the ability to produce/ understand musical sounds but retain the ability to produce/ understand speech. Other forms may affect rhythm, melody, pitch as well as the emotional aspects of music.

Melophobia refers to a fear of music. Non-academic sources typically want to add irrational to the description, and then describe symptoms as increased heart rate, an increased breathing rate, higher blood pressure, increased muscle tension, trembling and excessive sweating. Also included are increased anxiety thinking about or listening to music, as well as the avoidance of music. Proposed treatments include exposure therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, anti-anxiety medications, meditation, yoga, exercise and caffeine reduction.

The reason why I take melophobia seriously, and the main reason why I dislike the term irrational being used with it, is the use of melophobia as a mechanism to control violence, in A Clockwork Orange (1962). The protagonist, Alex, is subjected to aversion therapy. He eventually becomes severely ill at the mere thought of violence, but is also prevented from enjoying classical music. The book’s author, Anthony Burgess (1917 – 1993), was a composer, as well as a novelist. Some of the depicted violence in this works can be considered a re-creation of the rape of his pregnant wife, Llewela Isherwood Jones (1920 – 1968), by four American soldiers in 1942, that resulted in the loss of their unborn child.

A film version of the book, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1928 – 1999), appeared in 1971. Another version, depicting even more violence, can be found in a fan-made version of the computer game, Grand Theft Auto 5: Online, from 2015.

While it is fifty years since I have seen the film and attempted to read the book, which remains an uncompleted task, the world seems to imitating the worst aspects of A Clockwork Orange. As I study Ukrainian on Duolingo, I am periodically reminded of Nadsat = -надцать = -teen, a fictional language used in the book and film, with many terms originating in Russian.

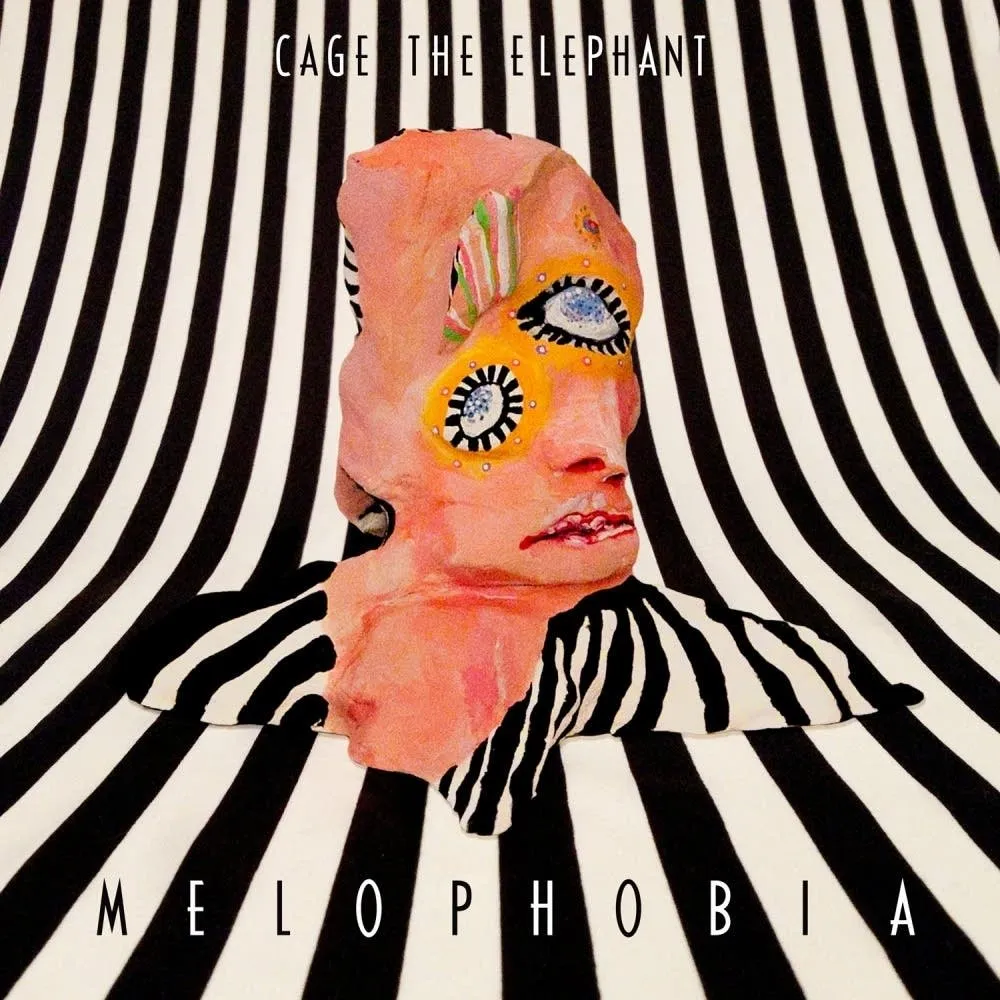

Fortunately, there are also positive developments. Natallie Kopp (ca. 1992 – ) provides a different, 21st century, feminine perspective on Melophobia that counterballance A Clockwork Orange. First, she informs readers that she is listening to Melophobia by Cage the Elephant [in 2013] for probably the 325th time.

Then she comments: Cage the Elephant didn’t mean a literal fear of music when naming the album Melophobia. In an MTV interview, [Matt] Shultz [(1983 – ), the group’s frontman] said he viewed the term more as denoting “a fear of creating music to project premeditated images of self, like catering to cool…rather than just trying to be an honest communicator.”

Kopp provides her own definition: a fear of looking bad musically, messing up in public, making the mistakes required for experimentation in a society where your projected image is supposed to bring grown men to their knees.

While I don’t accept the definitions provided by either Shultz or Kopp, I appreciated Kopp’s story, towards the end of her essay. She tells about volunteering at a week-long rock camp for girls and gender non-conforming youth, to lead a comedy workshop. Despite, some of the campers never playing a musical instrument before, in the course of this week they form bands, write an original song, and perform it in front of the rest of the camp in a joyous final concert.

She concludes by admitting that she experiments with sounds: some raw, some weak, some beautiful, some original, and allows her mind to fill in what is missing: accompanying instruments, perfect pitch, a sense of belonging, missed opportunities regained. The resulting music becomes louder than the words. She thinks about what it means to be loud and to be a woman, to be heard/ listened to with authentic imperfection. Her essay gives hope.

For many years, when I wanted to relax I listened to modern classical music, exemplified by Henryk Górecki’s (1933 – 2010) Symphony 3, Op. 36 = Symphony of Sorrowful Songs = Symfonia pieśni żałosnych (Polish) (1976 ). It is not as if I have only listened to classical music. I have allowed other people to impose their musical tastes on me when working, especially students in classroom situations. At home, children had a similar effect. In addition, I have sometimes chosen to listen to other varieties of music, but not normally to relax!

Yet, by constraining myself to listening to a narrow band of music for relaxation purposes, I had imprisoned myself. When I abruptly shifted to listening to other forms of music, exemplified by Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit (1991) music video, I discovered something unexpected. This forbidden fruit, as it were, eased unwanted mental states, including anxiety and depression. Soon after, I took an interest in music anhedonia, and then other related audio challenges.

Recently, I purchased a synthesizer. It was not to become a musician, but to experiment with sounds. Like Kopp, I expect some sounds will be raw and weak. I don’t expect many to be beautiful or original. Yet, I agree with her that such an instrument allows the mind to fill in what is missing. It has also freed me from some of my expectations. I felt better able to enjoy my present situation, and to accept my fate.

Background

I am a person who has had a tinnitus diagnosis since the age of 50. I learned to live with it fairly quickly. I also live with a person (Trish) who has experienced another hearing disability since about the age of 40: a hearing loss that prevents her from comprehending mid-range sounds, essential for understanding speech. This disability has also eliminated her previous interest in music. Until she lost her hearing she played the piano and guitar, and sang.

To help Trish cope with her hearing situation, there is no background music played in our household. When I listen to music alone, it is always through a headset. I am careful not to play any type of music loudly, because this can worsen my tinnitus.

When Trish and I watch videos together, it is an activity that could involve up to 100 hours a year. I tried to track viewing hours for the past two weeks, but the total number of hours was zero. When we do watch something it is usually a single documentary, lasting up to an hour. I can’t recall the last time we watched a movie or a television series. I do remember watching Tiger King, with my son, Alasdair, although some would also classify this series as a documentary.

Most video content contains incidental music. To watch videos we use a media centre that supplies audio content to a hearing loop that allows heading aid users to receive signals directly in their hearing aids. In addition it is connected to speakers that, optionally, allow signals to be transmitted to a headset.

Many people editing videos do not seem to realize just how disruptive music can be for a person with a hearing disability. Music often overwhelms the spoken content. Thankfully, most videos we watch are now texted. In the worst cases, we turn the sound off, and read the text.

For those obsessed with clinical details

Some researchers report that while wanting or anticipatory deficits correlate with abnormalities in hippocampal, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal regions. while liking or consummatory deficits correlate with abnormalities in the ventral striatum and medial prefrontal cortex.

Auditory agnosia is caused by bilateral damage to the anterior superior temporal gyrus, part of the auditory pathway for sound recognition. In some patients deficit was restricted to spoken words, environmental sounds or music. There is evidence that each of the three sound types (music, environmental sounds, speech) could be recovered independently.

Determining if a person has amusia involves taking a battery of six subtests assessing pitch contour, musical scales, pitch intervals, rhythm, meter, and memory. An individual is considered amusic if they perform two standard deviations below the mean of musically-competent controls.

This weblog post was originally written: 2021-06-05 at 10:20. It was revised 2022-11-06 starting at 20:30.