Bert, Albert Lancaster Lloyd, was an English folk singer and collector of folk songs. He appears in this weblog post as a key figure in the folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s, especially with respect to protest songs. This weblog post is being published on the fortieth anniversary of his death, 2022-09-29.

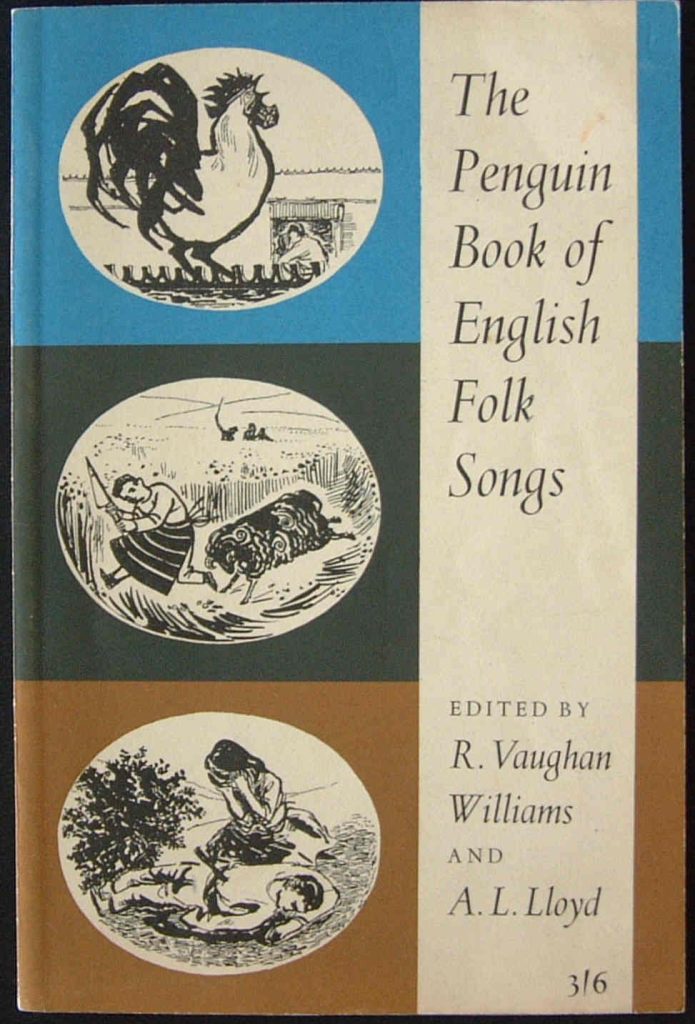

At one level, The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs (1959) is Bert’s claim to fame. Yet, I read into the title page, edited by R(alph) Vaughan Williams (1872 – 1958) with the assistance of (Bert) A. L. Lloyd. The two editors are not equals, especially in England, the arch class society, as lived in the 1950s. On Goodreads, the book has attracted two reviewers. Paul Bryant gives it five stars, but seems to think listing song titles constitutes a review. V gives it three stars, then writes, “Now all I need to do is find some friends to drink with[,] then sing these [in a] lout-ish manner. In all seriousness though, it’s well laid out with a large notes section.” V, at least, understands that songs have emotional content.

I have not prioritized purchasing this book, but own its replacement, The New Penguin Book of English Folk Songs (2012) by Steve Roud (1949 – ) and Julia Bishop (? – ). On Goodreads, Paul Bryant also gives this book five stars, then comments: “Folk music is a bitterly fought over territory. The original peasants who knew this folk stuff were located and taken into protective custody by some Victorian clerics and given the third degree until they sang like canaries. The clerics then deleted anything that looked like smut and published some of it for thrusting young schoolboys and schoolgirls to sing before they took jobs with the Foreign and Colonial Service and died of dysentery and malaria. Meanwhile some communists began to complain that all this folk was reactionary wimping about love and saucy milkmaids and lords and ladies with cranberries growing out of their brains, and pointed out that factory workers and miners had also made up folk about blacklegs getting their guts spilt. Then other communists, ones with typewriters, said that vicarfolk was all made up by Percy Grainger and Sabine Baring-Gould who used to beat each other’s bare flesh with glove puppets. Folk song? Au contraire, I think you mean fake song! they said. Then some people claiming to be Bob Dylan said that folk was still happening and they proved it too. Then some marketing departments decided it was a good label to stick on anyone who wasn’t actively taking heroin, because a label of folk guaranteed that an album would sell at least 23 copies. So people who once leaned against a pile of unsold Joan Baez albums while they were not waiting for their man were now called folk. It didn’t matter that they’d all written their own songs and played them on saxophones, it was folk if the marketing department said so.”

Kitchen scales do not decisively measure a quality difference between two books. Yet, quantitative measures impact one’s appreciation. The original book has 128 pages, while its replacement has 608. In the General Introduction of the replacement, Roud writes on the earlier work: “Vaughan Williams was one of the last survivors of the great days of the Edwardian folk-song collectors and the grand old man of the English musical establishment, although he died just before the project was completed. By contrast, Lloyd was a journalist and freelance writer who was one of the most vocal of the new Folk Revival activists, criticizing, questioning, and politically committed to spreading the word of folk song to the people.” (ix)

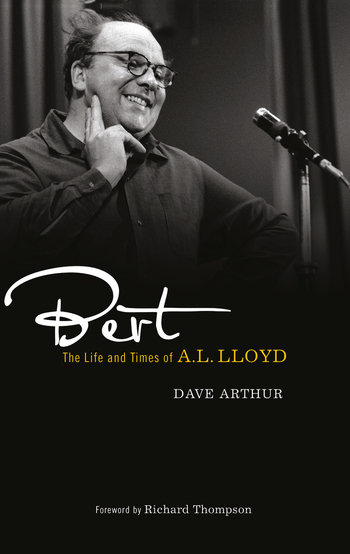

Dave Arthur’s (c1940 – ) book, Bert, the life and times of A. L. Lloyd (2012), provides insights into Lloyd’s life, in contrast to the Wikipedia article, that simply provides a summary. While the Wikipedia article about Bert can be read in a few minutes, it is Dave’s book that will provide a better understanding of his life and works.

Most of Bert’s family died early. In 1924, at the age of 16, after the death of his mother, and shortly before the death of his father, Bert was on his way to Australia on assisted passage, to find a new life as a farm labourer. Dave comments, “ … autodidacts like Bert are frequently such interesting people. Not bound by any ‘official’ canon or university reading list they are free to follow their noses and inclinations through half a millennium of printed books, and in the process explore bookish tributaries and bibliographic cul-de-sacs often missed by those more orthodox literary travellers who stick to the main routes.” (17) While accepting his fate as a farm labourer, he began to appreciate and collect Australian folk-songs. He also invested in HMV Plum Label (read: cheap) records, bought on speculation, to develop his musical understanding. He was not the typical sheep station hand. Immediately after the start of the Great Depression, in 1930, at the age of 21, Bert was back in England.

One of those insights provided by Dave about Bert is that Bert not always concerned about truthiness. For example, at times Bert described his father as a trawlerman = a type of deepwater, commercial fisherman. Dave mentions this, at the same time he presents evidence contesting it. Reading about it, I could not help thinking about a recent American president, an obsessed storyteller.

Libraries often devote large areas for the storage and presentation of literature, where truth is of secondary or lower importance. These collections are not referred to as lies, but as fiction. Individual books are often judged on their emotional appeal, not on how little they deviate from the truth. The same can be said about folk songs, and music more generally. People listen to music because of its emotional appeal, not its strict adherence to truth.

Sometimes, emotional content can be received negatively. In my lifetime, the song with the greatest negative impact is Vinger av stål = Wings of Steel, used by Braathens SAFE = South American and Far East Airlines, to celebrate their 50th anniversary, in 1996. It is so bad, that I cannot even find it on YouTube. I could relate to a song mentioning aluminum, titanium, carbon fibre, or even a more generic light-alloy wing. It is perhaps fitting that Braathens was out of business by the new millennium. For decades they had argued for increased competition in the European airline market. When that opportunity came, they found that they did not have the characteristics needed to succeed.

Bert was often described as a collector of folk songs. Yet, one must ask, what is a collector? Is it simply a synonym for historian? I think not. A collector has an emotional connection with the material being collected. The collection process often changes the content. Yet, the collector themselves may not appreciate how this works in practice.

Stephen Sedley (1939 – ) comments: “I think that both Bert [Lloyd] and Ewan [MacColl/ James Henry Miller (1915 – 1989), another folk singer and folk song collector,] were unnecessarily embarrassed about admitting that they were adding or improving when, of course, the whole folk process had always been a process of adding and improving.” (28)

Bert was soon a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. He developed a friendship with Arthur Leslie Morton (1903 – 1978), author of A People’s History of England (1938). My 1976 edition takes time to explain that the book originally stopped with the Spanish Civil War, while mine ends with the conclusion of World War II. In the previous century, politics was an import aspect of the folk music being collected.

One of my interests in life is a person’s relationship with technology. In his introduction, Dave describes some characteristics of Bert in terms of ca. 1972 audio equipment, a Swiss Revox reel-to-reel tape deck. At the time, this was the apex of amateur sound recording. The technological world fifty years ago was vastly different. Today, every hand-held device aka smartphone, has audio capabilities that only the finest (read: expensive) sound studios could offer in 1972.

Attitudes to audio recording collections have changed significantly from the mid-1950s to about 2 000. In this previous century, people often took pride in displaying their recorded music collections. These collections allowed visitors to see if there was any overlapping interest. If there was, it could become a topic of conversation.

In this previous century, many musical choices involve selecting an appropriate format. The 78 rpm record was launched in 1928; the 33 rpm 12″ LP in 1948; The 45 rpm 7″ disk in 1949; the compact cassette in 1963; and, the 8-track cartridge in 1964. Each of these increased the availability of popular music. Regardless of format, music consumption was limited by personal hardware and software investments. Even music from radio stations that became widespread in the 1920s and paid for by listening to advertisements, required investment in an AM radio. Wide-band FM radio offered high-fidelity broadcasting in 1933, but only became widespread after the introduction of FM stereo broadcasting in 1961. These formats continued to dominate music until the arrival of the 120 mm digital audio compact disk (CD) in 1982, which is forty years ago. In 1991, MP3, a coding format for digital audio developed largely by the Fraunhofer Society, an applied research institution, in Germany. This format was not tied to a physical device.

Neil Straus explains, that in 1995, material costs were 30 cents for the jewel case and 10 to 15 cents for the CD. Wholesale cost of CDs was $0.75 to $1.15, while the typical retail price of a prerecorded music CD was about $17. On average, a store received 35 % of the retail price, the record company 27 %, the musician 16 %, the manufacturer 13 %, and the distributor 9 %. Because of a perceived value increase, when 8-track cartridges, compact cassettes, and CDs were introduced, each was marketed at a higher price than the format they succeeded, even though the cost to produce the media was reduced. Apple marketed MP3s for $0.99, and albums for $9.99, because the incremental cost to produce an MP3 is negligible.

In terms of digital downloads, in 1997-09, Birmingham, England Duran Duran’s Electric Barbarella became the first paid downloaded digital single, following released Boston, Massachusetts Aerosmith’s Head First that was available without charge.

Musical preferences are often based on two principles: repetition and containment. Repetition allows songs/ tracks grow on people over time. Radio playlists reinforced repetition. Eager listeners would be exposed to multiple plays a day, for at least a week. It offers opportunity for new songs to ingratiate themselves.

Containment allows songs/ tracks to be closely associated with specific, other songs/ tracks. From my childhood onward, music has typically been contained/ bundled in an album format.

What is the 2022 replacement for a music collection? One answer could be Spotify, the proprietary Swedish audio streaming services founded 2006-04-23 by Daniel Ek (1983 – ) and Martin Lorentzon (1969 – ). Some users describe streaming services as a faucet/ tap/ spigot. One turns it on, and music comes out.

One challenge with streaming is that it eliminates, or at least reduces, repetition. There is so much choice available, that music is dismissed without given something a second chance. There is little opportunity to hear a track repeated.

Streaming replaces the album bundle/ container with the track, more specifically, one type of track labelled liked songs. There is no need for any form of continuity between any two liked songs. This makes the development of any emotional attachment between tracks difficult, if not nebulous.

Unfortunately, streaming can be an uncomfortable experience. Many have commented that accessing an infinite amount of music feels inappropriate. There seem to be two challenges, possibly related to our biological nature. First, there should be quantitative limitations placed on any collection. Yes, there should be some finite, max size. Second, content should be appropriately bundled.

Bert produced a large number of albums, that united the content. For example, The Iron Muse (A Panorama of Industrial Folk Song), is the title of two Topic Records albums. The first, an LP released in 1963, followed by a CD released in 1993. Topic Records is a British folk music label, that began as an offshoot of the Workers’ Music Association in 1939, making it the oldest independent record label in the world.

Some people may appreciate this streamed approach to music, but dislike how it is manifest on Spotify, or similar services. For those who appreciate their music direct from the spigot, but dislike the streaming provider, Navidrome could be a solution. It is a simple music library, that self-hosts an open source streaming service that uses a home server and a virtual private network (VPN) on a phone. It can stream from any location, across various devices. Physically, it is a box that plugs into a router. It holds everything from Bandcamp purchases to ripped CD tracks. Users of Navidrome often comment about moving away from Big Streaming to a broader movement that incorporates small-scale tech projects and open-source services that are not resource- or energy-intensive.

In the 1950s and 1960s, when I first became a consumer of music, there was only a limited selection available. That selection was limited by recording studios, to ensure their investments produced an adequate economic return. Then, radio stations limited their play lists. After all, the purpose of a radio station is not to provide listeners with free music, but to sell advertisements. Those who were actually interested in music, typically invested in vinyl records.

Approaches to finding new music in the 2020s typically involves the internet. Online music store Bandcamp provides revenue to many musicians, taking a smaller cut of sales compared with streaming services. The Bandcamp Daily blog is a useful tool to find interesting music.

Sometimes, other living human beings can provide new musical insights. Even if musical tastes differ, people can provide musical insights unavailable from an algorithm. While it might not be the best approach to start a conversation with a complete stranger, one can continue a conversation by asking a person to disclose their most interesting musical experience this week, possibly after divulging one’s own experience.

Local record stores don’t seem to exist here in Norway any more. Some white ware stores seem to have a small selection. Fortunately, there are a few used stores that do seem to offer a selection of used records. In Inderøy, we have Kjæringa me’ Straumen that has many musical gems in different formats, including CDs and LPs.

Other sources for music can be radio stations, local and physical or distant and online. They range from the ultra professional, to amateur. Univerisity/ college/ school stations may appeal to younger people, but there are also stations that are run be retired persons, that target music of specific genres and eras.

DIY! Hardware suitable for the recording and editing of vocal music can be acquired for less than NOK 1 000/ US$ 100. Almost everything can be made using open source software, and a few hardware components such as a basic microphone (suggestion, Behringer XM8500) on an old but quiet laptop. This is goodenuf quality! In many cases, especially in terms of folk music, there should be no copyright issues, especially if distribution is limited to family and friends.

‘

Notes

A minor character in this weblog post is Stephen Sedley. He lists carpentry, music, changing the world as his recreations. Novelist and screenwriter Ian McEwan (1948- ) is more enthusiastic about Sedley’s literary merits, commenting on Ashes and Sparks: Essays on Law and Justice (2011) “you could have no interest in the law and read his book for pure intellectual delight, for the exquisite, finely balanced prose, the prickly humor, the knack of artful quotation and an astonishing historical grasp.” Since about 2003, Sedley has been known, especially, for his Laws of Documents, to be read as humour:

- Documents may be assembled in any order, provided it is not chronological, numerical or alphabetical.

- Documents shall in no circumstances be paginated continuously.

- No two copies of any bundle shall have the same pagination.

- Every document shall carry at least 3 numbers in different places.

- Any important documents shall be omitted.

- At least 10 per cent of the documents shall appear more than once in the bundle.

- As many photocopies as practicable shall be illegible, truncated or cropped.

- Significant passages shall be marked with a highlighter which goes black when photocopied.

- (a) At least 80 per cent of the documents shall be irrelevant. (b) Counsel shall refer in Court to no more than 5 per cent of the documents, but these may include as many irrelevant ones as counsel or solicitor deems appropriate.

- Only one side of any double-sided document shall be reproduced.

- Transcriptions of manuscript documents and translations of foreign documents shall bear as little relation as reasonably practicable to the original.

- Documents shall be held together, in the absolute discretion of the solicitor assembling them, by: a steel pin sharp enough to injure the reader; a staple too short to penetrate the full thickness of the bundle; tape binding so stitched that the bundle cannot be fully opened; or a ring or arch-binder, so damaged that the arcs do not meet.

In Norway, the government switched off analog radio signals in 2017. It was the first country in the world to end FM consumer radio transmissions. Millions of old radios were made obsolete, while consumers were encouraged to purchase new DAB+ radios. Here at Cliff Cottage, we have a DAB+ radio, bought specifically for use during emergencies. If we remember, it is tested annually, then put away until the next year.

The English translation of the name of Kjæringa me’ Straumen, would be something like, the woman with the tide. It comes from Kjerringa mot strømmen which expresses the opposite, the woman against the tide. Originally, this was the title of a Norwegian folk tale published by Asbjørnsen and Moe in 1871. Kjæringa is the Trøndersk dialect pronunciation and spelling, of a term variously translated as woman, wife or (especially in other dialects) hag. In Trøndelag, the term is viewed positively. Straumen is the name of our village, but means the same thing as strømmen = tidal current.