Since the first set of 5 weblog posts was published about optics, I have made some changes about upcoming post content. This weblog post is the sixth in a series. It is about analogue cameras; Future posts : #7 is about binoculars, but also includes opera glasses, monoculars and spotting scopes, scheduled for publishing 2025-01-18; # 8 is about astronomical telescopes, scheduled for publishing 2025-01-25; #9 is about microscopes, scheduled for publishing 2025-02-01. Later, two additional posts will appear: #10 is about digital cameras, scheduled for publication on 2025-03-01.; #11 is about digital photograph collections, scheduled for publication on 2025-03-08.

As I started preparing to write this post, my mind was comparing analogue photography with riding a horse. Something obsolete. However, I then began to remember that much of my photographic career was dependent on using specific types of cameras for very specific purposes. So yes, this is about analogue = film cameras.

My main objection to film cameras is the expense of film purchase and processing. In contrast to the camera that comes with almost every handheld digital device = smartphone, the marginal cost of taking an image is almost zero. Admittedly, those images have to stored somewhere, hopefully in multiple places.

Reminder: The 3-2-1 rule/ data protection strategy = save three copies of data, stored on two different types of media, with one copy kept off-site. This is very expensive to do with analogue photographs, especially if the negatives are missing. Flatbed and slide scanners can create digital copies inexpensively.

In general, a high quality colour image of 2 400 x 4 000 pixels can be reduced in size, without reducing quality, to occupy less than 1 MB, A 10 TB hard disk costs NOK 3 500 or less, and can store 10 million of these images at a cost of about NOK 0.00035/ image. That is about 1/300 of a cent/ image. Yes, one should keep three copies for backup purposes, which raises the cost to 1/100 of a cent.

Film

Unprocessed film is a perishable product that can be damaged by high humidity and high temperature. Fresh film is better able to provide true colour. Film should remain unopened in its original canister or plastic wrap. To protect against humidity, include a silica gel desiccant bag in the film storage container. Reuse of desiccant bags is possible.

Yet, because of a digital revolution, it was not always possible to buy film, so people attempted to preserve the film they had available. The situation in 2025, is much improved compared to 2005. In much the same way that some people prefer to listen to antiquated LP records played on turntables, some people like to revert to antiquated film technology.

Film that is expected to be used in less than 6 months, could be stored in a refrigerator at 8°C or lower. For longer term storage, years rather than months, a freezer can be used at -18°C or lower. Before use, film stored in a freezer, should be placed in a refrigerator for 24 hours. Film removed from a refrigerator, should be given 2 hours or more to adjust to room temperature. At one time, even after I had gone over to digital cameras, I had stored rolls of 35 mm Fuji slide film in our refrigerator, just in case. Currently, our refrigerator hosts one undated roll of Illford Pan F film.

Film available in 2025

Here are some notable films being manufactured

ADOX 20, a black and white film with ISO 20. “No other film is sharper, no other film is more finegrained, no other film resolves more lines per mm (up to 800 L /mm).”

Fuji one of only two remaining major manufacturers of colour film. The film range currently comprises: Consumer films = FujiColor/ FujiColor Superia and Professional films = Neopan, Velvia and Provia. Instax is a range of instant films and cameras launched in 1998 which now outsell the traditional products.

Kodak was established in 1888 and is the other major manufacturer still producing colour film. While these are manufactured in Rochester, New York, since its bankruptcy in 2012, distribution and marketing is controlled by Kodak Alaris, a UK based company, acquired in 2024 by Kingswood capital management. The film range is divided into Consumer films = ColorPlus & Gold/Ultramax, and Professional films = Tri-X, T-MAX, Ektar, Portra & Ektachrome.

Background

Analogue cameras are dependent on using light to create an image on film. Film is used as a generic term, because sometimes a film emulsion is placed on glass plates, or even a piece of metal. At Vangshylla, one of the local farmers has a hobby of using a 4″ x 5″ camera, with glass plates to produce images. I have assisted him once, to take a photo of his family, with him in it.

Personally, I have no intention of reverting to analogue photography again, even if I have stored the equipment needed to develop film in our attic. These items are historical objects to show people how humanity has progressed, technically.

Twentieth century photographic techniques

Photography uses a lens to capture a lighted image on a photographic plate in a camera. It is analogous to images passing through the lens of an eye, to create an image on the retina. In much the same way that it can be advantageous to live in a lighted room, sometimes additional light is needed to create a suitable photograph. A common approach is to attach an electronic flash. An important characteristic of photographic film is its light sensitivity, revealed in its ISO number. The actual amount of light hitting a photographic plate is determined by the shutter speed and the aperture opening. Both of these can be adjusted on most advanced modernish analogue cameras.

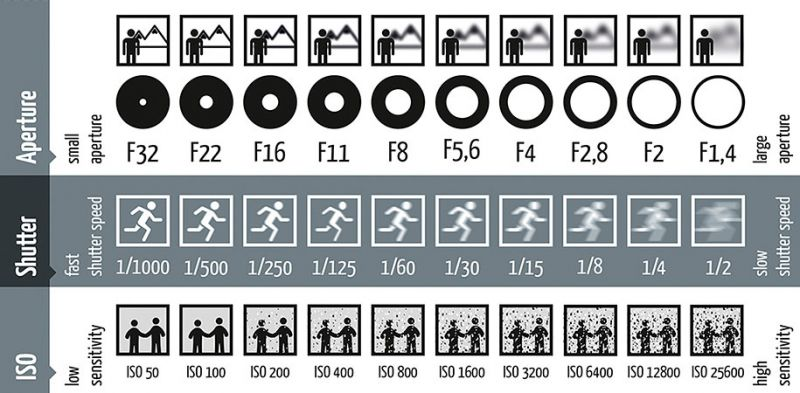

Shutter speeds are expressed as fractions of a second, a higher shutter speeds means a faster shutter speed, a shorter period of time that an aperture is open. Typical values are shown in the image below, typically starting with 1/1 000 and ending with 1/2 s. Most films did not produce normal results if the film speed is longer than 1/15 s. Speeds of 1 s or more are often referred to as time exposures. Shutter speeds of a longer duration, introduce blur in objects that are in motion.

Aperture openings are also stated numerically. The smaller the number the bigger the opening. Therefore, an f/1.4 is a very large opening while f/22 is a very small opening. A small opening is necessary to provide focus at depth. Large openings have a very limited focal depth.

Some people like to describe exposure in terms of a bucket being filled with water. The aperture is analogous to an adjustable hole that opens and closes at the top. The duration of the hole remaining open is analogous to a continuous stream of water entering the bucket. The smaller the hole at the top, the longer the hole would need to be open to fill the bucket with water. Conversely, a larger hole will need a shorter amount of time to fill the bucket. So in this analogy the water pouring in represents light. A full bucket of water is a properly exposed image.

Film speed is the measure of a photographic film’s sensitivity to light. The ISO, referring to the International Organization for Standardization, system was introduced in 1974. It combined a linear ASA = American Standards Association, scale used in the United States, with a logarithmic DIN standard 4512 by the Deutsches Institut für Normung used in Europe. Almost since its introduction, the DIN component has often been dropped.

The ISO arithmetic scale means that a film with an ASA 200 rating needs only half the light of a film with an ASA 100 rating. However, film with a higher rating, produce images with more grain.

Both the ASA and DIN systems have a long history, and many revisions. DIN goes back to at least 1934, but with links to The Scheinergrade system devised by the German astronomer Julius Scheiner (1858–1913) in 1894. It uses a logarithmic scale. My direct experience of ASA starts with PH2.5-1960, but versions of it date back to 1943.

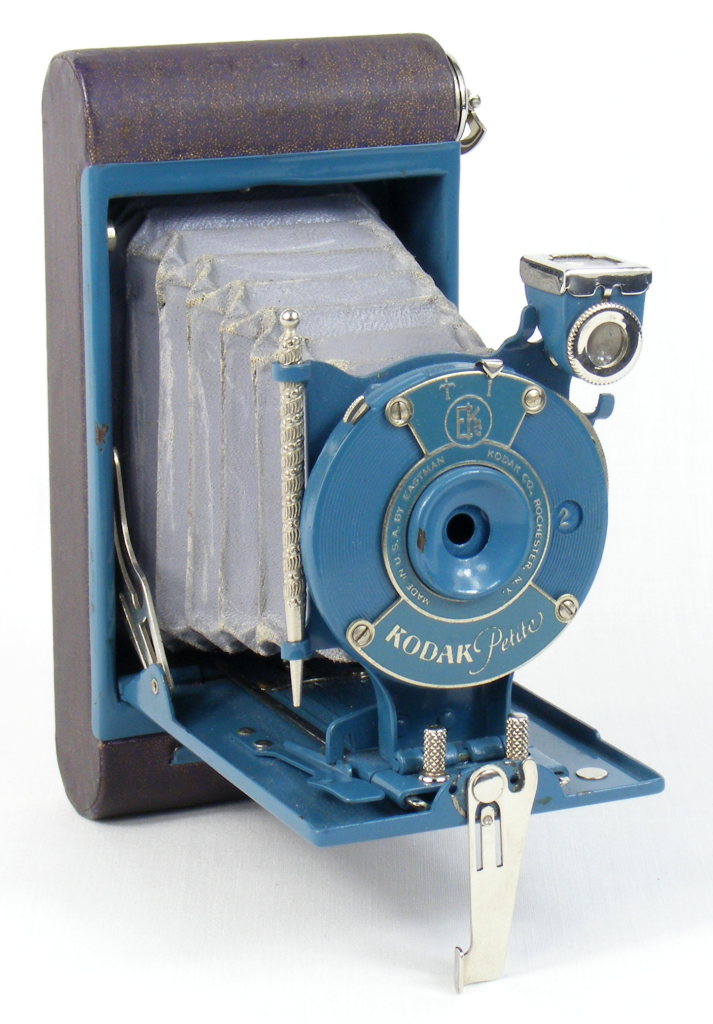

The camera I remember best from my youth, shown at the beginning of this post, was my mother’s Kodak Petite, made between 1929 and 1934. Since she was born in 1916, I imagine it was purchased towards the end of this time period. It was equipped with a bellows, and used 127 film, which was 46 mm wide. It produced negatives that were 40 x 60 mm. The reason I used this was to take photomicrographs, especially of small marine and fresh water plants that I had collected trailing a plankton net behind my 2.4 m long Sabot sailing dinghy. I used black and white film exclusively. This camera rested on the eyepiece of my microscope, while a 30 second time exposure was made.

More modern cameras suitable for use with modern microscopes will be discussed in Optics 9 Microscopes, scheduled for publication on 2025-02-01.

In grade 12, I was tasked as the official student photographer for my high-school newspaper and year book, I used a 35 mm camera for the first time. It was a Contax II, that was used with Kodak Tri-X black and white film with high speed 400 ASA, which was purchased in 35mm x 100 foot lengths. In the school darkroom, I would load film onto cassettes. Because the camera lacked flash possibilities, dark situations often required that I push the film to ASA 1600, and develop it accordingly. Unfortunately, this increased the film’s grain structure. Kodak, attempted to market this as adding a level of realism to photographs. I was never convinced.

I developed all of the film I used, then spent numerous hours making prints with an enlarger. Working alone, and in the dark, except for a red light, this was the process I liked the most. In essence an enlarger is a camera with a light at the top, that projects a negative image onto photographic paper. One could set the aperture opening, and the exposure time. In this case there was a large timer that controlled the light inside the enlarger, then counted down the seconds before turning off the light. It was 1960s automation.

I am not sure how many times I visited the local camera shop on 6th Avenue in New Westminster. I was interested in an Asahi Pentax Spotmatic camera. It used a Through The Lens (TTL) centre-weighted light meter. This camera allowed one to focus the lens at maximum aperture with a bright viewfinder image. After focusing, a switch on the side of the lens mount stopped the lens down and switched on the metering which the camera displayed with a needle located on the side of the viewfinder. This stop-down light metering was innovative, but it limited the light meter, especially in low light situations. A M42 screw-thread lens mount was used to accommodate high quality Takumar lenses. This meant that it took considerably longer to change lenses, than with a bayonet mount.

Exakta VXIIb

Unfortunately, I could never afford to buy a Pentax. Some years later, in 1973 or so, I bought my first camera, a used Exakta Varex IIb called an Exakta VXIIb in USA. It was a 35 mm camera, produced between 1963-67, and referred to as version 6. Film speeds could be set on the top of the shutter speed dial. Shutter speeds followed the modern geometric progression from 1/30 to 1/1000 second. The rewind knob has a crank handle, but there was no view-finder release knob. The camera did not have a built-in metering system, but I had a hand-held light meter. Despite, this limitation, I especially liked the camera for two reasons. First, it came with a bayonet mount system for interchangeable lenses. Second, and more unusually, it allowed interchangeable view-finders. I had two, a pentaprism as used on most 35 mm cameras, and another one that allowed viewing from the top. This was especially useful when I studied archaeology, because it could take photos of an archeological excavation’s stratigraphy = cultural layers.

Exakta is no longer a recognizable brand, but James Stewart (1908 – 1997)/ L. B. Jefferies and Grace Kelly (1929 – 1982) / Lisa Fremont used one attached to a Kilfitt 400 mm f5.6 lens in Alfred Hitchcock’s (1899 – 1980) Rear Window (1954). It is one of the most iconic cameras in film history.

With this new camera, I switched to Illford Pan F black and white film with ASA 50 film speed, which, with its fine grain, suited my personality better. I have never been a user of colour negative film, but with this camera used Ektachrome, a slide/ transparency film that was developed by Kodak in the early 1940s. It allowed both professionals and amateurs the opportunity to process their own films. I always used the ASA 64 version, because it gave better results than High Speed Ektachrome, announced in 1959 with ASA 160. At the time, many north Americans were Kodachrome enthusiasts. However, it required professional processing.

Ektachrome processing is simpler, and small professional labs could afford equipment to develop the film. I used the E-6 process variant. which allowed amateurs with a basic film tank and tempering bath to maintain the temperature at 38 °C, to obtain suitable results.

Yashica FX-2

After Trish and I married, we bought ourselves a modern Yashica FX-2 35mm single lens reflex (SLR) camera. This type of camera was manufactured in Japan, starting in 1976. It was Yashica’s second camera to use the new bayonet lens mount known alternately as the Contax/Yashica = C/Y mount. The intended advantage was that one could start off with inexpensive Yashica lenses, then progress to better quality Contax lenses when finances allowed it. In reality, one stuck with Yashica lenses because they were more robust than the more delicate Contax lenses.

Its viewfinder provided 0.89x magnification and nearly 90% field of view. The through the lens (TTL) light meter used Cadmium sulfide (CdS) as a photoconductive material in its photoresistor. The film speed could be set from 12 ASA to 1600 ASA. There is not much film that is sold over 400 ASA. However, this allowed users to set the film speed that the film woud be developed at. This is an important characteristic for that group of people.

The results of this metering was shown with a needle on the right side of the viewfinder display. When a proper shutter speed and aperture opening combination was selected, a proper exposure would result with the needle between the + and −. Manual focus is provided by manually turning the lens to the left (closer) or right (further away).

One could always see how a particular aperture opening would affect focus by pressing a depth of field preview button, located at the base of the lens. The light meter was powered with a 1.3v mercury battery (EP-675R, RM-675R, or equivalent) located underneath the camera, Its housing could be opened with a coin. Yes, younger readers may need to understand that smaller units of currency involved small round pieces of metal that were often carried in wallets or pockets. These days it would be considerably easier for me to find a slotted screwdriver than a coin. Yes, technology changes.

It was a very easy camera to use, and conventional for the period. The focal plane shutter operated from 1/1000 to 1 sec and B = bulb. If one needed a longer shutter opening than 1 second, then one set it to B, and held the shutter open for as long as one wanted. To use it properly, the camera would have to be mounted on a tripod, with the exposure made using a cable release. A flash could by synchronized by using X sync at speeds from 1/60 and slower. A self-timer was built into the camera. This gave the photographer about 10 seconds to position her/himself.

The mass of the camera body (without lenses) = 690 g. Camera dimensions were: 144.5 x 94 x 51 mm.

With this camera, my darkroom career almost ended, although I continued to develop black and white film. For colour slides, we increasingly used Fujichrome, usually Fujichrome 64.

Tripods

While I have learned to brace myself to take photographs without tripods, they are useful! Of course, to take full advantage of a tripod, one should use a cable release = threaded cable release = a device used to actuate the shutter of a camera without touching the shutter button. It consists of a flexible wire moving within a sheath, with a threaded connector on one end, an a plunger on the other. The sheath is usually vinyl. It is purely mechanical, in contrast to an electronic remote shutter release.

At one time I found a used tripod on sale for less than a reasonable price, I bought it, so that I could give it away to someone with an unmet and often unrealized need. So, my gift suggestion is for people to stock up on unusual, inexpensive used items that can be given away. They make much nicer gifts than yet another box of chocolates that people will despise you for because they went up an additional 100 g, eating those unnecessary calories!

This is the last camera that will be discussed here. We bought one additional 35mm SLR camera before entering the digital age. It claimed to be more modern, but my favourite camera will always remain the Yashica FX-2.

In much the same way that I have an aversion of audiophiles, who claim to hear music much better than their anatomy is capable of perceiving, there are terms to describe two types of annoying users of cameras. In Swedish, the term linslus with lins = lens & lus = louse, refers to someone obsessed with being photographed. In English, that person could be called a lenslouse. A person obsessed with taking photographs is a shutter bug. It is a kinder term, if only because I include myself in that category. These two terms cover annoying people in front of, or behind the camera, respectively.

Yes, I would like to encourage other people to share their thoughts/ experiences about analogue photography, by making comments or sending an email to me.

On 2024-04-27 this post was scheduled to be published on 2025-01-04 at 12:00. Sometime later that was changed to 2025-01-11 at 18:00.