In mythology, Avalon is an island, dominated by Arthur’s sister, the sorceress Morgan. It is also the location where Arthur’s sword Excalibur was made, and where Arthur recovers from injuries suffered at the Battle of Camlann. This weblog post has nothing to do with mythology, but the Newfoundland peninsula of the same name, visited by Alasdair and myself starting 2024-07-19. In particular, this looks at three features: the Newfoundland Coastal & Railway Museum, Signal Hill and Cape Spear. Heart’s Content, where the first transatlantic cable between Europe and north America landed, is also situated on this same peninsula, but it will be discussed in a subsequent post, Newfoundland, currently scheduled for 2024-10-05.

Prologue

After walking from the Travelodge to the north terminal at Gatwick, England, in half the time it took to walk there, we were soon boarding our Westjet 737 flight to Newfoundland. This was the fastest flight I have ever taken to North America from Europe, at about 4h 30m. That is, if north America excludes the western/ north American section of Iceland containing KEF = Keflavík airport, and consider all of Iceland as being in Europe.

I have a fascination with some islands and archipelagos. In Canada, I have lived and worked on Vancouver Island, which is where my father was born. I have visited Cape Breton Island, where my McLellan ancestors arrived in the Margaree Valley, over 200 years ago, from South Uist, an island in the Hebrides. Queensborough, part of New Westminster, but not the part where I grew up, is located on Lulu Island. It is, however, the location of the machine works run by my wife Trish’s maternal grandfather.

It took me until this year, at the age of 75, to visit Newfoundland, which has been waiting as a Canadian island to cross off from a bucket list. I have a relationship to it, as both of my parents – Jennie and Mac – served there in the Royal Canadian Air Force, during the second world war. They were married in St. John’s in 1942. Earlier, Trish’s father worked on freighters taking paper from Corner Brook to other places in the world.

On the Westjet 737, I was seated in a middle seat, towards the rear of the aircraft, between Alasdair and Buckers. I had not met Buckers before, but learned she was English, and would be continuing her journey on to Jasper, on another Westjet aircraft, in a matter of hours after her arrival at St. John’s.

Later, we would learn that Jasper had been devastated by wildfires. We also experienced our share of live disinformation, when we were incorrectly told by other tourists that 84 people had died in the fires, and that the arsonist responsible for starting the fires had been arrested. I find it distressing that people can’t be bothered to check facts. My current understanding is that there were two fires, one to the north, another to the south, that met near Jasper. The fires resulted in one death, firefighter Morgan Kitchen (2000-07-23 – 2024-08-03) who died as the result of a falling tree. This occurred after we returned to Norway. At the time of writing, 390 square kilometers were said to have burned, along with 358 structures. No official cause of the fires had been released, and it was under investigation.

When we landed at YYT, St. John’s International Airport, our first task was to acquire our rental vehicle which turned out to be a Ford Explorer, with a 4-cylinder 2.3 litre engine. We were not especially impressed with the vehicle, in part because it consumed large quantities of fuel, and did not respond well with its adaptive speed control. On a more positive note, Newfoundland’s infrastructure for electric vehicles was not built out, so I should be thankful that we opted for an ICE vehicle.

We then needed to eat a meal, which occurred at a local A & W, immortalized in the photo above. Rootbeer is the only beverage I miss from Canada, after 44 years of living in Norway. I drink it to excess when in north America, knowing that it could be several years before I experience it again.

After dinner, we found our accommodation: two rooms with kitchenettes, at Crossroads. This housing complex seemed to have been designed for weekly commuters, coming from the outports, but working in the St. John’s metropolis.

Railway & Coastal Museum

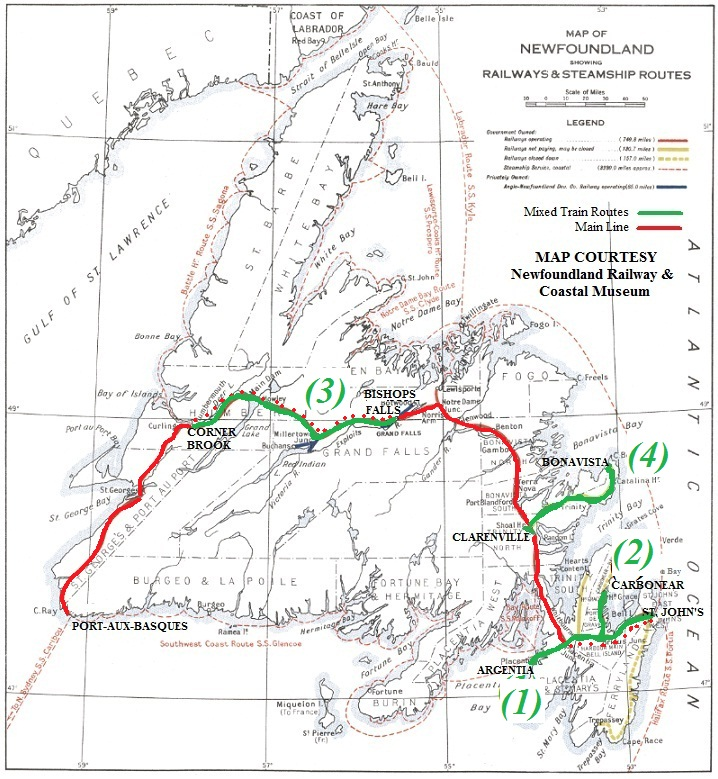

On 2024-07-20, we drove into downtown St. John’s. Our first stop of the day was at the Newfoundland Railway &Coastal Museum, the former railway station. There haven’t run trains on Newfoundland since 1988. The railway was augmented with ships, which is why the term coastal is applied to the museum.

The Newfoundland Railway was a narrow-gauge railway that operated in Newfoundland from 1898 to 1988. It had a total track length of 1 458 km. It used 3′ 6″ gauge = 1 067 mm.

Prior to leaving Norway, Alasdair had purchased, and I had read Les Harding’s (? – )book: The Newfoundland Railway, 1898-1969: A History (2014). It provided a good overview of the topic. The museum exhibits kept reinforcing the content in the book. I was less impressed with the rolling stock on display.

Prior to leaving the museum, Alasdair had purchased three additional books about rail transport in Newfoundland, all written by Kenneth G. Pieroway (? -): Rails Around the Rock (2014), Streetcars of St. John’s (2019) and Trains of Newfoundland (2022). We do not have his first book: Rails Across the Rock (2013).

The challenge with rail transport in Newfoundland is that most of the economic development is at points along the coast. This favours ships rather than rail cars. There is also a need for a highway network allowing for the shipment/ distribution of goods, as well as the transport of people. Much of this need for transport is provided by the Trans Canada Highway (T.C.H.), and other highways. In comparison to Norway, travel time is 50% faster in Newfoundland (typically 90 km/h vs 60 km/h). The highways are also wider and straighter.

The low population of Newfoundland means that there is no advantage gained by having two forms of land transport, road and rail. Thus, visiting the railway related exhibits at the Newfoundland Railway and Coastal Museum is a look backwards in time. There is no future on the island for rail!

Signal Hill

On 1901-12-12, at Signal Hill, in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Guglielmo Marconi (1874 – 1937), listening through his telephone headset, heard a series of three dots, Morse code for S. He had received the first transatlantic communication, from a radio transmitter in Poldhu, Cornwall, England, about 3 500 km away.

This incident illustrates a major challenge. It is easy to propagate and send radio signals. It is more difficult to receive them, and that challenge increases with distance. Marconi was especially drawn to the work of Heinrich Hertz (1857 – 1894), on the transmission of electromagnetic waves through the air.

Marconi started experimentation with wireless telegraphy in 1894. He realized that although messages could be transmitted over long distances through wires, there was great potential in sending messages wirelessly, especially to ships. He discovered that signal range could be increased by grounding the transmitter and increasing the height of the antenna. While born in Italy, he had an Irish mother. Both of his parents had British citizenship. Thus, it was natural for him to move to England in the late 1890s, in part because the Italian government failed to support his work, probably because he lacked a university education.

In 1896 he patented his first wireless telegraphy machine. In 1897 he founded the Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company to manufacture these devices, which were radio sets capable of transmitting and receiving messages in Morse Code. The Royal Navy quickly saw the potential of this technology, and in 1899 equipped three of their warships with these radio sets. Commercial shipping companies quickly followed the Navy’s lead.

A common misconception about radio anno 1900, was that radio waves would travel in a straight line, limiting their distance from the point of origin to the horizon. Marconi believed that radio waves would follow the curvature of the earth. This meant that messages could travel much greater distances. The main focus at the time was on being able to communicate with ships at sea. Even though Marconi believed this to be possible he still had to prove it. His idea was to send a message across the Atlantic, where there could be no doubt that the waves were bending with the curvature of the earth.

The Royal Navy’s decision to try Marconi’s wireless radio systems was based on the success of his 1899 experiment where he transmitted a message across the English Channel to France. It was still unknown how far a wireless signal could be sent.

For a transatlantic transmission, a receiver was set up at Cape Cod, Massachusetts. However, a storm damaged the antenna at Poldhu forcing Marconi to replace it with a shorter one. Because of his doubts about the capability of this shorter antenna, Marconi changed the receiver location to Signal Hill, Newfoundland. A signal was to be sent each day at an appointed time from the transmitter in Poldhu. Simultaneously, Marconi would try to receive the message. The antenna had to be lifted into the air by balloons and kites. High winds resulted in several failed attempts, until they didn’t, and a message was successfully received.

Marconi correctly believed that radio waves followed the earth’s curvature, but misunderstood the mechanism. Waves travel along the ground and through the air. It was not the waves that traveled along the ground that allowed the message to be received but the waves that traveled through the air bouncing off the ionosphere.

With this success Marconi’s company flourished. Newfoundland wanted Marconi to set up a wireless station on the island, at Cape Spear. This did not happen due to a preexisting monopoly agreement between the government and the Anglo-American Telegraph Company where Anglo-American received a fifty-year monopoly on telegraphic communications on the Island in exchange for running a cable from St. John’s to Newfoundland’s west coast and across the Cabot Strait connecting Newfoundland to the rest of North America. This agreement did not expire until 1904, and the company threatened to sue Marconi if he tried to establish a wireless station on the island before that time. To avoid this Marconi decided to construct his station at Glace Bay, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia.

Marconi build a telegraph station at Cape Race, Newfoundland in 1904, after the Anglo-American Telegraph Company’s monopoly expired. On 1912-04-14, this station received the distress signal from RMS Titanic.

Marconi made a couple of more trips to Newfoundland to conduct experiments to improve wireless telegraphy and telephony (the transmitting of the human voice) until his death in 1937. Additional insights can be obtained by looking at the Newfoundland Heritage webside, including works by Jeff Webb (2001), and Jenny Higgins (2008). Books on the subject include: Arthur C. Clarke ( 1958) Voice Across the Sea (first edition 1958, second edition 1974); K. W. Hoffman, History of Telecommunications in Newfoundland (1978); Michael McCarthy, Frank Galgay and Jack O’Keefe The Voice of Generations: A History of Communications in Newfoundland (1994).

St John’s Harbour Symphony

While at Signal Hill, we had an opportunity to hear the St. John’s Harbour Symphony, part of the bi-annual Sound Symposium festival with a distinctive sound, now celebrating its 40th anniversary. This is performed daily, for five minutes, one week a year, at 12:30 each day. Volunteers board ships in port and make music using ship’s horns.

Pieces performed are composed using a unique system. Monotone horn blasts are marked as dots in a grid, with each box representing one second. The claim is that this allows music to be accessible for non-musicians. Activities are divided between volunteers. Some will count seconds while an assigned partner operates a horn. Happenstance is part of the Harbour Symphony experience: Sometimes a ship doesn’t show up as planned; sometimes, a horn doesn’t work. Uncontrollable variables result in improvisation.

While I initially found it irritating, I missed it when it was over, five minutes later. Regardless, there is no escaping the Harbour Symphony in downtown St. John’s, or at Signal Hill. Ships are an integral part of St. John’s environment. They have been sailing there for 500 years. Until the cod crisis, they were integral to Newfoundland life, with a mix of the controlled and the chaotic .

Cape Spear

Yes, we had to visit Cape Spear with its eatery, lighthouse, signs, WWII fortress and significance as the most easterly point in Canada, at least since 1949-03-31: 52°37′11″West. At my birth, Labrador and Newfoundland were not part of Canada. At that time, the most easterly point in Canada was at the Quebec-Labrador border, near Blanc-Sablon, longitude: 57°06’30” West. We visited both places on this trip. Americans can also gain bragging rights at Cape Spear, as it is in contention as the most easterly place in north America. In the contiguous United States, the farthest east anyone can travel is Sail Rock, Lubec, Maine: 66°56′49.3″W. Even further east is Point Udall, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands at 64°33′54″W. Both these places ignore Alaska, and Amatignak Island at 179°8′55″W.

Cape Race

We never visited Cape Race, and the Myrick Wireless Interpretation Centre. It claims to enlighten visitors about the earliest days of wireless communication and telegraphy in Newfoundland. It is named for the Myrick family who lived and worked at Cape Race from 1874 to 2007. Cape Race involves a 155 km/ 2h20m trip from St. John’s, in each direction.

The problem we encountered with Cape Race, was its failure to provide essential information, such as opening times, and a description of the interpretation centre experience. One does not travel long distances anno 2024, in the hope that a venue will be open when one arrives. Similarly, without a description of activities, it is impossible to know if a museum will succeed or fail to tell an interesting story. The last thing anyone wants is a well laid out collection of facts. Listening to some reconstructed version of a mayday signal from RMS Titanic, is not my idea of a well-spent afternoon.

Note : Stop researching for a while and begin to think! Advice from /. = slashdot.org as I started working on this series of posts: I have tried to follow that advice.

“It is more difficult to receive them, and that challenge increases with distance. Marconi was especially drawn to the work of Heinrich Hertz (1857 – 1894), on the transmission of electromagnetic waves through the air.”

The coherer detector Marconi used is another example of something that when you first hear about it, you think, “That cannot possibly work!”

As a fellow visitor to historic sites, I must underline your comment about visiting sites that are vague as to open times and what they actually contain.

But, as usual … perhaps it is due to the amount of detail routinely included … the element that caught me eye was how young Hertz was when he died.