This weblog post is being published on the 30th anniversary of Brook Stevens’ death on 1995-01-04.

I did not start out admiring Brook Stevens. Instead, I admired a car, then found out that it had been designed by Stevens. In my opinion, Stevens was more of an industrial designer than a vehicle stylist. He was working with companies that could afford to use complex processes in large, well financed plants, as well as other companies that often had to outsource processes that larger companies would perform internally. He also had to know how the products he designed would be used. That said, not all of his designs were successful. The worst one was the Jeepster!

Stevens had a very severe case of polio at the age of eight. For a time he was unable to walk without help, but after a regimen of exercise (especially swimming) he regained almost full mobility. He always had a limp and suffered stiffness and pain in one half of his body. Towards the end of his life, more severe symptoms returned and he was eventually forced into a wheelchair. Stevens was encouraged by his father to draw while confined to bed. He studied architecture at Cornell University, at Ithaca, New York, from 1929 to 1933. Then, in 1934, he established a home-furnishings design firm in Milwaukee.

When he started working with vehicles in the mid-1940s, after the end of the second world war, he was working with unconventional products, including Harley-Davidson motorcycles in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Willy-Overland jeeps in Toledo, Ohio. He later worked with Studebaker, in South Bend, Indiana.

Stevens role at Willys was subordinate to Chief Engineer, Barney Roos (1888 – 1960). Roos had served as Studebaker’s head of engineering from 1926 to 1936, specializing in straight-eight engines. He later worked for the British Rootes Group in the design of Humber, Hillman and Sunbeam Talbot cars. Before World War II, he returned to the United States, where he co-designed the Willys MB.

The Willys MB and the Ford GPW, were both formally referred to as the U.S. Army truck, 1⁄4‑ton, 4×4, command reconnaissance. They were commonly known as the Willys Jeep, Jeep, or jeep. They were sometimes referred to by its Standard Army vehicle supply nr. G-503. Whatever they were called, they were highly successful American off-road capable, light military utility vehicles. 640 000 were built to a single standardized design, for Allied forces in World War II, from 1941 until 1945.

Much of the success of Willys jeep was its use of the L134 Go-Devil engine. This was probably the company’s greatest asset.

The engine started life as a less than impressive 36 kW 4-cylinder automobile engine. Roos increased its performance and durability beyond the Quartermaster Corps specifications of 115 Nm of torque at the rear axle. The extra power made it the engine of choice for the U.S. Army. It ended up as a 2.2 litre undersquare = 79.4 mm bore x 111.1 mm stroke engine with an L-head design with valves parallel with the cylinders. Initial power output was 45 kW at 4000 rpm and 142 Nm of torque at 2000 rpm. Compression = 6.48:1. In the Utility Wagon power was increased to 47 kW. This L134 engine was phased out by the F-head Willys Hurricane engine beginning in 1950.

An oversquare engine has a bore that is larger than its stroke. This allows larger valves and more space for air and fuel to enter and exit the cylinders, potentially leading to higher horsepower at higher RPMs due to the increased airflow. Undersquare engines with a longer stroke typically produces more torque at lower RPMs, which can improve its pulling power.

Stevens was influenced by he streamlined style of Stevens’ early work owes a great deal to New York designers who emerged in the 1920s, such as Walter Dorwin Teague (1883 – 1960), Norman Bel Geddes (1993 – 1958), Raymond Loewy (1893 – 1986) and Henry Dreyfuss (1904 – 1972). He was more especially influenced by European custom automobile designer, Alexis de Sakhnoffsky (1901 – 1964) born in Kyiv, Ukraine. Stevens owned a car, made by the Cord Automobile Company of Indiana, that Sakhnoffsky had customized. He met Sakhnoffsky in Chicago in 1934. He was impressed to learn that automotive design could pay over $300 a day. Stevens early car designs were sometimes quite reminiscent of Sakhnoffsky’s creations, that emphasized streamlining. For a short period in the 1950s Sakhnoffsky worked for Stevens as a staff designer.

Stevens had his office in Milwaukee because of its proximity to manufacturers. Allen-Bradley, Harley-Davidson, Cutler-Hammer, and Edmilton were among his early clients, that were all located in Milwaukee.

He worked more as a sales person, than a designer. He had a support staff of about twenty. After being hired to design/ redesign a product, he would usually make some quick sketches, showing the basic lines of the new design, with an emphasis on the product’s look and function. A staff designer would make renderings from these sketches, often using an airbrush or marker. Stevens would then meet with the client and decide which version was best. Next, a three-dimensional model, either at scale or in full size, would be made by an in-house model-maker. Initially sculpting clay was used, but in the 1960s the firm used cast fiberglass. Then, the model was painted/ embellished.

I share one trait with Stevens, a love of peanut butter. However, he was frustrated by jars that had a too narrow neck, so it was impossible to get all the peanut butter out of the jar’s shoulders. Stevens insisted on a wide mouth.

When Willys’ made their prototype jeep shortly after USA entered World War II, it was overweight compared to Army requirements, but the powerful engine and its heavier and more robust transmission, was a power train combination that proved to be beneficial in the long-run for use in cross-country travel.

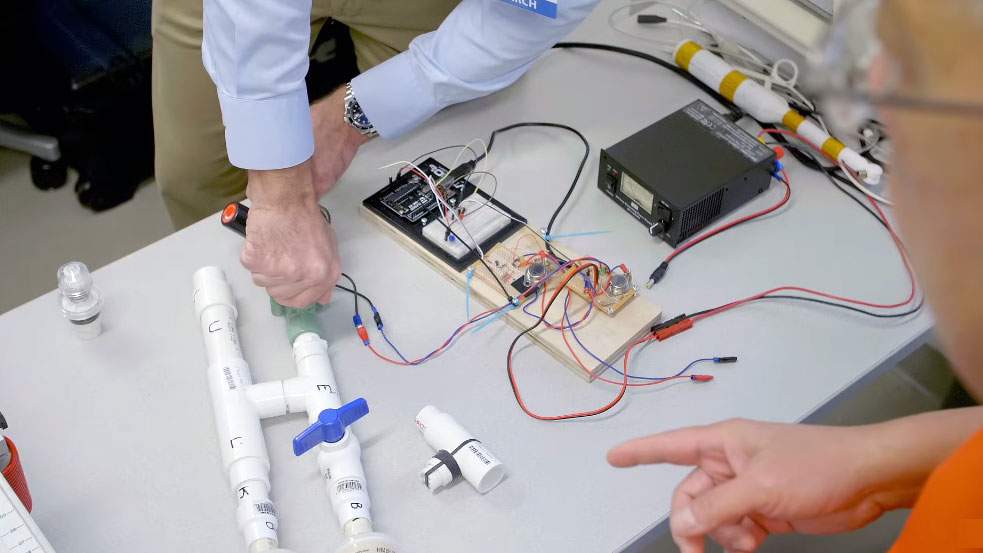

Willys did not have their own facilities for automotive bodywork. Their sheet metal manufacturing processes were outsourced to appliance manufacturers. These fabricators were restricted in terms of the shapes they could produce. Body panels could not have an offset of more than about 150 mm. In sheet metal drawing, a die forms a shape from a flat sheet of metal, the blank. This material is forced to move and conform to the die. Pressure is applied to the blank and lubrication applied to the die or the blank. Wrinkles will occur in the part, if the blank moves too easily. The correction is more pressure or less lubrication to limit the flow of material and cause the material to stretch. Too much pressure will result in the part becoming too thin, leading to breakage. Drawing metal requires finding a balance between wrinkles and breaking to produce a useful part.

To be a successful automotive designer, Stevens had to understand many different production processes: conventional sheet metal drawing, deep drawing, piercing, ironing, necking, rolling and beading.

Confession: I have attempted to buy one American car in my life, a 1956 Willys Station Wagon (rear-wheel drive). Unfortunately, my savings were just too little to afford it. I have also been attracted to some American vehicles produced by: International Harvester, Rambler, Studebaker and Willys. The Big Three = General Motors/ Ford/ Chrysler? Not so much.

This vehicle was in production from 1947 as the Willys Station Wagon (model 463), using the same engine and transmission, and with clear styling influence from the CJ-2A Jeep. The CJ in the model description refers to civilian jeep. In 1948, a Jeep Utility Truck emerged. Both it, and the wagon were available in four-wheel drive. In this formation it was referred to as a Utility Wagon the ancestor of all sport utility vehicles. It was an all steel vehicle, with a fake woody body.

A Jeepster convertible, model designation VJ, was also available from 1948 to 1950, with rear-wheel drive only, and the 4-cylinder Go Devil Engine. VJ apparently doesn’t mean anything. Wikipedia tells us the Jeepster’s problems in the marketplace were due to its limited utility and practicality. It looks rugged and off-road capable, but is not. Appeal is limited due to the basic construction, poor all-weather protection, and the low performance when equipped with the I-4 engine. Even with an optional six-cylinder engine and offering the VJ3 version at a lower price, Jeepsters did not draw many new buyers. One specific factor turning potential buyers away, was the lack of roll-up door windows.

Brooks also designed Harley-Davidson motorcycles, especially the 1949 Hydra-Glide, one of his first, helping create the new suspension forks in the front, bucket headlight, and the streamlined design. All Harleys since, including models in production now, are based on Stevens’s body designs.

Stevens worked with branding. His most ambitious projects were an ongoing series of package and logo designs for Miller Brewing in the early 1950s. For 3M he developed a unified package design, that was applied to 35 000 different products, in 1965.

Stevens started working for Studebaker in 1961, when the company was already in a lot of trouble financially. The auto manufacturer closed its South Bend factory in December of 1963. Thus, the only Stevens designs that Studebaker produced were the 1962 and 1963 Larks and Hawks and the 1963 Wagonaire. He did create several prototypes for other cars, projecting designs for the company all the way out to 1968.

Stevens’ relationship with Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) was always extremely strong, in part because he was a friend of Ralph Evinrude (1907 – 1986). Stevens’ staff designers, especially Gordon Kelly and John Bradley, executed hundreds of designs for OMC’s products: Evinrude and Johnson outboard motors, Lawn Boy mowers, Cushman scooters, carts and motorcycles.

Stevens acknowledged the fact that all of his designs were ephemeral. He envisioned good design as changing from year to year, to adapt to new technologies and new tastes. Planned obsolescence was