Norges Naturvernforbund (NNV) = The Norwegian Federation for Nature Conservation is Norway’s oldest nature and environmental conservation organization. NNV is a democratic membership organization with over 35 000 members The members are the foundation of the organization and carry out the local work. The members are organized in local branches, which in turn are organized in county branches. This weblog post celebrates its founding exactly 111 years ago on 1914-02-18. However, activities only started two years later, in 1916.

The organization works on a wide range of issues, including area protection, watercourse protection, species protection, climate emission reductions, energy saving, transportation, environmental toxins, forestry, fishing and farming. The Federation also works internationally, with partner organizations, notably in Russia, Ukraine, Togo and Mozambique.

The Federation for Nature Conservation is the parent organization of Natur og Ungdom (NU) = Nature and Youth founded on 1967-11-18, and also established Miljøagentene = Environmental Agents, for children, in 1992. Originally, it had been called Blekkulfs miljødetekiver = Blekkulf’s environmental detectives, with Blekkulf being the name of a cartoon octopus. I translate the name as Bleached Wolf. It also helped with the founding of the Rainforest Fund and a Development Fund. It is affiliated with Friends of the Earth, one of the world’s largest networks of environmental organizations.

NU was to work for environmental protection.

NNV consists of county and local branches as well as a national secretariat. The organization has county branches in all of the country’s counties, and a total of about 100 local branches. A local branch can cover one or more municipalities.

The Norwegian Federation of Nature Conservation’s highest authority is the national congress, which meets every two years. Between national congresses, the association is led by a national board with representation from the county branches, and by a central board with five members. The head of both of these is the organization’s elected leader. There is also a secretary general who leads the daily operations of its secretariat, which is located in Oslo. Most of the approximately 30 employees are based there.

For the first 50 years, the Nature Conservation Association was an organization for a few, but professionally qualified members who were mainly engaged in classic nature conservation. In the 60s and 70s, however, the organization began to work on a much broader range of issues and became more critical of the government’s environmental protection work. Among other things, oil pollution, acid rain and river development = damning, were put on the agenda.

A critical change occurred at Mardala, a small valley named after the pine martin (Martes martes). It was the site of non-violent political actions against electrical power development in the summer of 1970 in Eikesdal = Oak Valley in Møre og Romsdal county. The action was an important symbolic event for the importance of preserving untouched nature. The action became particularly well-known because of the high Mardalsfossen waterfall in Eikesdal, which was to be put in a pipe, to be turned into electricity.

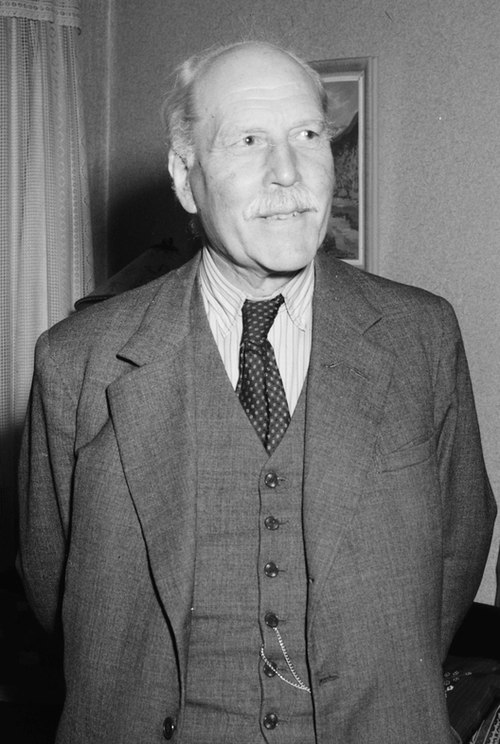

The Mardøla action was ideologically motivated, non-violent direct action, which made it unique at the time. The actions used civil disobedience as a means of resistance against power development, which was new in Norway. The leaders of the action were removed by the police after a camp was organized along the route of the construction road. Among the several hundred protesters were several well-known people, including philosophers Arne Næss (1912 – 2009) and Sigmund Kvaløy Sætreng (1934 – 2014) as well as the politician Odd Einar Dørum (1943 – ). The action was supported by the local population in Eikesdal and Eresfjord. But the actionists had to withdraw after threats from other Romsdal residents, especially there was resistance in Rauma municipality which wanted to get income from the power development.

The watercourse was developed and Mardalsfossen is dry most of the year. Only a few weeks during the tourist season each summer 2 m³ per second of water is released into the waterfall. The old water flow could be significantly greater, 40 m³ per second was not uncommon during snowmelt.

Protests against the development of hydroelectric power were much of the basis for building up an effective nature and environmental protection movement in Norway.

The waterfall is by the south end of the lake Eikesdalsvatnet, which also can be seen in the photograph. The waterfall’s total drop is 655 metres. The largest free fall is 297 meters, which is among the tallest in Norway.

The next significant action was called the Alta controversy, involving a plan by the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) to construct a dam and hydroelectric power plant, creating an artificial lake inundating the Sámi village of Máze. After political resistance, a less ambitious project was proposed that would cause less displacement of Sámi residents and less disruption for reindeer migration and wild salmon fishing.

When work on the project started again in 1981-01, more than one thousand protesters chained themselves to the site . The police responded with 10% of all Norwegian police officers being stationed in Alta, quartered in a cruise ship. Protesters were forcibly removed by police. For the first time since World War II, Norwegians were arrested and charged with violating laws against rioting. The central organizations for the Sámi people discontinued all cooperation with the Norwegian government. The Norwegian Supreme Court ruling in favor of the government in 1982. Organized opposition to the power plant ceased, and construction of the Alta Hydroelectric Power Station was completed by 1987. Despite this, the government lost the ethical war, especially among intellectuals, with respect to its racist anti-Sámi policies. Because of their civil disobedience, four leaders, including Per Flatberg (1937 – 2022) from Inderøy, were sentenced for encouraging illegal acts.

This conflict put Sámi rights over lands in Northern Norway, as an indigenous people, onto the national political agenda. With the passing of the Finnmark Act in 2005 the Sámi made important long-term gains, and revived interest in their culture. In addition, the conflict unified environmental groups.

The Fosen wind farms discussed here are about 100 km to the north-west of Cliff Cottage. Article 27 of the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) has become the most important international provision for the protection of indigenous peoples’ cultural practices. This article was central to the Norwegian Supreme Court’s consideration of the case concerning wind power plants on the Fosen peninsula in 2021-10. This was a historic decision because it was the first time that affected Sámi parties, in a case concerning a development project in their traditional areas, won in the Supreme Court through reference to human rights. This judgment is central because it clarified several key issues regarding indigenous peoples’ protection against interference in their traditional reindeer grazing areas.

The Supreme Court Fosen judgment, from 2021, concerned the validity of the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy’s decision from 2013 to expropriate and grant a licence to the Storheia and Roan wind power plants on the Fosen Peninsula. The windfarms are located in an area where reindeer husbandry is practiced. The herders claimed that the construction interfered with their right to enjoy their own culture according to Article 27, but this was rejected by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy in 2013. Although the issue was brought before the courts, the company was nevertheless permitted to start the construction, and the windfarms were ready in 2019 and 2020, respectively. They are part of the largest onshore wind power project in Europe.

The case before the Supreme Court concerned whether the construction of the Fosen windfarms amounts to a violation of the reindeer herders’ right to enjoy their own culture under Article 27 of the ICCPR. The ICCPR is incorporated into the Act Relating to the Strengthening of the Status of Human Rights in Norwegian law (the Human Rights Act) of 21 May 1999. ICCPR thus applies directly as Norwegian law. It also takes precedence over other Norwegian legislative provisions through Section 3 of the Act in the event of a conflict with them. A grand chamber of the Supreme Court unanimously found a violation of Article 27 and stated that the licence and expropriation decisions were invalid. As of 2025, the Wind Farms are still in place, producing energy and profits for the companies that own them.

What surprises many is the ingrained racism of Norwegian society, especially with respect to Sámi people, and the attempt by the Norwegian government to Norwegianize this population. However, this racism is also directed to other ethnic groups, particularly Gypsies and immigrants from the Middle East. Rather than receiving assistance to conform to Norwegian laws, these ethnic groups, have had their children taken away and placed in institutions or foster homes, for violating parential laws, particularly related to corporal punishement. Even when the Norwegian Government loses cases at the European Court of Human Rights = the Strasbourg Court, the international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights, lights do not always start to flash.

In the future people should expect other environmental cases to emerge. Some will involve the extraction of petrochemicals in environmentally sensitive areas, others will involve the extraction of minerals, and the use of fjords to dispose of mine tailings. NNV will undoubtedly need to spend more time (and money) advocating its principles in court, than linking members to equipment or fences in the field, or outside Stortinget = the Parliament, to protest damage to the environment.

While the Norwegian population supports offshore wind projects, these can be more expensive to build, and more complex to extract energy from, than the proven technology of onshore wind farms.