Homebound was sent as an entry in Bella Caledonia’s Scotland 2042 competition that describes Scotland in twenty years time, in 2042. In my letter accompanying the work, I asked it to be considered in the human category. This was because the organizers had wanted to distinguish three categories of writers: men, women and under 25 years of age. There was also a size limit of 1000 words. The submitted document’s word count was 998 words, 6 179 characters including spaces, 5 187 characters without spaces. That left two words to spare!

Bella Caledonia has existed an online magazine publishing social, political and cultural commentary since 2007-10, at the Radical Book Fair in Edinburgh. It was launched by Mike Small and Kevin Williamson (1961 – ). It also existed as a 24-page print magazine, at one time as a supplement to the Scottish pro-Independence newspaper, The National. This print version ended in 2017. It was named after Bella Baxter, a character in Alasdair Gray’s (1934 – 2019) novel Poor Things (1992). Gray later provided the site with a new version of his artwork.

The origins of Homebound date back to 1974. Working as a student archaeologist, I lived at one of the notorious Canadian residential schools, in Port Alberni, British Columbia. However, this school was not regarded as one of the worst! Other schools subjected First Nations children to inhumane treatment, that resulted in genocide. The Alberni Indian Residential School, as it was officially called, opened in 1890 under the Presbyterian Church. It burned down in 1917 and was closed for three years. In 1920 it was re-opened under the United Church. It officially closed in 1973. Many of the workers at the archaeological site had attended this school.

In preparation for this submission, I checked the current fertility rate in Scotland, and elsewhere. Without children, there is no future for humanity, but fertility has to be kept within bounds. In 2020, the latest date for which I could get figures (mainly from CIA produced, World Factbook), it was 1.29. The fertility rate for some other countries with name, rank and fertility-rate: Ireland, 124th, 1.94; United States, 141st, 1.84; Norway, 142nd, 1.84; China, 184th 1.60; Russia, 185th, 1.60; Canada, 193rd, 1.57; Ukraine, 194th, 1.56; Japan, 214th, 1.43; Taiwan, 226th, 1.14; and Singapore, 228th and last, 0.87. Total fertility rate (TFR) is “the total number of children that would be born to each woman if she were to live to the end of her child-bearing years and give birth to children in alignment with the prevailing age-specific fertility rates.” A TFR of 2.1 is regarded as a replacement rate. Thus, none of the countries mentioned here seem capable of replacing their populations. In Japan, many regard automation as the answer, in other places, it is immigration.

This submission focused on race relations, especially the negative impact of British colonization on First Nations people. Racism has also impacted many others, notably Chinese and East Asians (including British subjects from India, whose denial of entry into Canada was illegal, but supported by Canadian and British Columbia governments). With the word count limiting one’s freedom of expression, I opted to focus on First Nations. In a future post, I intend to discuss how colonial racism impacted the Chinese community.

One notable opponent to Asian immigration, from New Westminster, was former Premier, Richard McBride. He had many places named after him including a village, a mountain, a park, two schools and a boulevard. One of the schools, Richard McBride Elementary School in New Westminster was built in 1912 as a replacement for the Sapperton School. After it burned down, it was rebuilt, a task completed in 1929. In 2018, provincial funding allowed this school to be replaced.

There was, however, discussion about the name for the school. In a letter dated 2020-06-22, the Richard McBride Elementary School Parent Advisory Council writes:

During his time as premier (1903 to 1915), McBride advocated for “a white B.C.” and sought to shut out the “Asiatic hordes.” He worked hard to prevent “cheap” Japanese labour from competing in the fisheries and in “everything the white man has been used to call his own.”

McBride led the legislature in passing numerous anti-Asian measures, such as taxes on companies that hired Chinese labourers and legislation denying the vote to Asians and Indigenous people.

After the Conservatives formed the federal government in 1911, McBride urged Prime Minister Robert Borden to honour a promise to legislate against immigration from Asia.

McBride was premier at the time of the Komagata Maru incident, when the Japanese steamship carrying hundreds of Sikh passengers was prevented from docking and most of its passengers were barred from entering B.C. McBride was quoted as saying: “To admit Orientals in large numbers would mean the end, the extinction of the white people.”

As premier, McBride pursued a policy of making way for economic development and the expansion of cities by dispossessing Indigenous nations of their reserve lands.

McBride was also well-known as a leading anti-suffrage politician at a time when white women were gaining the vote across Canada. He believed extending the franchise to women would take away too much power from men.

Richard McBride Elementary School no longer exists. Long live, Skwo:wech Elementary School, opened at the beginning of the school year in 2021-09. The name means sturgeon in Halq’emeylem (the upriver dialect), a language understood by the local Qayqayt First Nation, but not actually in hǝn̓q̓ǝmin̓ǝm̓ (the downriver dialect). The school serves over 400 Kindergarten to Grade 5 students from the Sapperton neighbourhood in New Westminster. In promotional materials, it is stated that the school offers “diverse programs that support the social, emotional and academic enrichment of students. We feature both Montessori and regular programs, and host the StrongStart Early Learning Centre. Our Goal at Skwo:wech is to work together to foster a positive school community of socially and emotionally connected learners.”

The name connects people with Sto:la = Sturgeon River = the Fraser River, central in New Westminster’s history. Sturgeon represented a primary food source for Indigenous communities, before commercial fishing in the early 1900’s overfished them for their caviar. It is a slow moving, but long-lived fish, there is a sense of resilience. The name itself also reflects a value necessary for reconciliation, with a name that honours local Indigenous practices, culture and contributions. Sturgeons are also an integral part of Coast Salish myth. Some have also pointed out similarities between schools of fish and schools of learners.

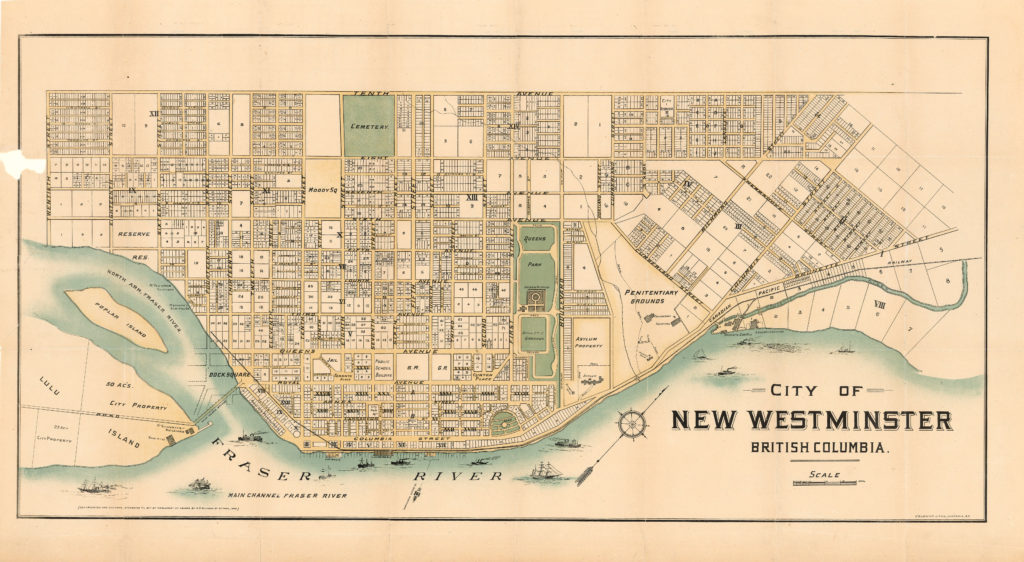

The above map of New Westminster, is oriented as many of its citizens perceive their city, with the west on the left and the east to the right, with the north at the top, and the south at the bottom. Streets run south to north, avenues from east to west. Even numbered addresses are on the southern and western sides, odd numbered on the northern and eastern sides. Unfortunately, even these basic facts aren’t actually true. The compass near the bottom of the map helps explain it. Most streets run from the south-east to the north-west; most avenues from the north-east to the south-west. The exception is Sapperton, on the right of the map, where streets run in their true north-south and east-west orientation.

New Westminster was founded by the Royal Engineers, led by Colonel Richard Moody (1813 – 1887), to be the capital of the Colony of British Columbia in 1858, and continued in that role until the colony’s merger with the Colony of Vancouver Island in 1866. New Westminster was the largest city on the mainland, from that year until it was passed in population by Vancouver during the first decade of the 20th century.

The most prominent street on the map of New Westminster is Fifth Street, where my sister lives. The architecture is attractive. Some patriots might even call it majestic with traffic divided by a boulevard. This was to be lined with foreign embassies, but by 1871, when British Columbia entered Canada, this dream came to an end. Victoria had become the capital of the united colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia.

This weblog post ends with the submitted story,

Homebound

On board the sky blue C-5M Galaxy transport plane on its daily flight, scheduled to arrive at GLA, Glasgow Airport, at 10 in the morning, were Eileen Erskine, 97, her son Jack, 65, her grandson Nathan, 40, and his wife Ivy, also 40, and their daughter, Freya, 8. They were five of yet another 200 Canadian refugees being ferried in that day, this time the weekly flight from Vancouver, part of the four million that Scotland had agreed to repatriate. Each of them had their allotted 100 kg of baggage.

During the first two years of the flights only young, fully trained construction professionals arrived. They were the fore-troop, building out the housing and infrastructure for those to come later. Eileen had been born in Glasgow towards the end of the Second World War. Her parents had immigrated with her to Vancouver, where she had grown up. As housing prices escalated, she had been forced into the interior of British Columbia. Today, housing anywhere in Canada was worth nothing. The various First Nations own everything, the result of a Canadian Supreme Court ruling.

Refugee flights also arrived from Toronto and Halifax. Most of the passengers had been living in refugee camps in Canada since the beginning of 2040. The Erskines were allowed in now because Eileen had been born in Scotland.

When Britain gave reciprocal British citizenship to Australians, Canadians and New Zealanders, the First Nations of Canada, renamed the Canadian Nation, saw their opportunity to depopulate their sovereign country.

Deciding where all of the refugees should go was complex. People could apply for a particular country and location, but it was an algorithm that decided. Many of the refugees destined for Scotland, had one ancestor from there, often a result of highland clearances. Most were ethnically mixed, commonly with English, Irish or even Welsh, but often involving more exotic combinations. Many Scots-Irish were assigned to Scotland, despite arriving in Canada from Ulster. Everyone had to be moved by 2050. At its current rate only sixty thousand people made it to Scotland, in a year. That rate would have to ramp up to six hundred thousand a year, ten flights a day, to meet the timeline.

With all of these new immigrants, Scotland finally took action against the lairds. No corporation, family or individual could own more than one hectare; houses could not exceed 500 square meters. Excess lands and buildings had to be sold to local authorities, who could then either sell them onwards, or rent them out.

Similar flights were being made to the other British republics: Cornwall, England, Mann, Northumbria and Wales. European Canadians from France, Germany and most of the other countries still in the United States of Europe (USE), were not being treated this way. USE was skilled at getting its own way, but to its disadvantage. They, too, needed new immigrants because of the fertility crisis.

In Scotland, developing a green economy and repopulating the Highlands and Islands were priorities. Silicon Glen would extend into Silicon Highlands and assorted island offshoots. People with proven connections to the Lowlands, such as Eileen and her family, moved there. Greenness involved building wooden houses out of plantation woods such as Douglas-fir and Sitka Spruce, then rewilding Scotland with native species. It also involved growing several iterations of crops a year using hydroponics, and fish using aquaponics.

Bureaucrats loved the opportunity to create exceptions. Refugees thought to have connections to the Hudson Bay Company, were sent to the Orkneys, which was prime recruitment territory for the fur trading company. Of course, not all of these descendants were required to leave Canada. Those with First Nations heritage were allowed to stay in Canada, something a DNA test could prove.

Fur traders were not the worst of immigrants to Canada, if only because of their dependency on native trappers. Gold miners were often only interested in get-rich-quick schemes. When these failed, as they most often did, the former miners took to homesteading, taking the lands already occupied by the First Nations people, and often giving them European diseases that killed them off.

The Canadian Nation dealt more harshly with Scottish descendants, in part because the first prime minister of Canada, born John Alexander McDonald in Glasgow, infuriated past and present indigenous people, because federal policies he enacted, encourage their genocide, from gold miners, settlers and the residential school system.

With the Canadian Nation owning all of the land in Canada now, it was payback time, and the descendants of British settlers suffered the most. Except it wasn’t suffering at all. Scotland needed young workers!

Immigration reinforced English. Scots and Canadians spoke the same language, although with different dialects and vocabularies. At the Canadian refugee camps they were educated in green skills that could be put to immediate use on their arrival in Scotland. They also received a social education that gave them an understanding of Scottish history, but also a history of the European exploitation of Canada, and how this negatively impacted the First Nations peoples.

One of the many concerns was how long it would take the new citizens to drive comfortably on the left side of the road. Native born Scots wondered how many lives would be lost before the new immigrants consciously looked right, first, before crossing roads. Some worried that an upcoming plebiscite would change the country to driving on the right. The new citizens were restricted to autonomous vehicles. An agreement with Stellantis, and a reconstructed Linwood auto factory resulted in a new, electric and autonomous MPV, the Hillman Husky: a brand name that united the past with the future, a model name that appealed to most Canadian refugees, and a product that looked after most transportation needs.

Eileen soon arrived at her new home, an assisted living centre, in Laurieston. The tenements she had grown up with had disappeared, as had the towers that replaced them. “Absolute luxury,” she declared, as she ate her dinner of haggis, neeps and tatties, “Its good to come home, finally.”