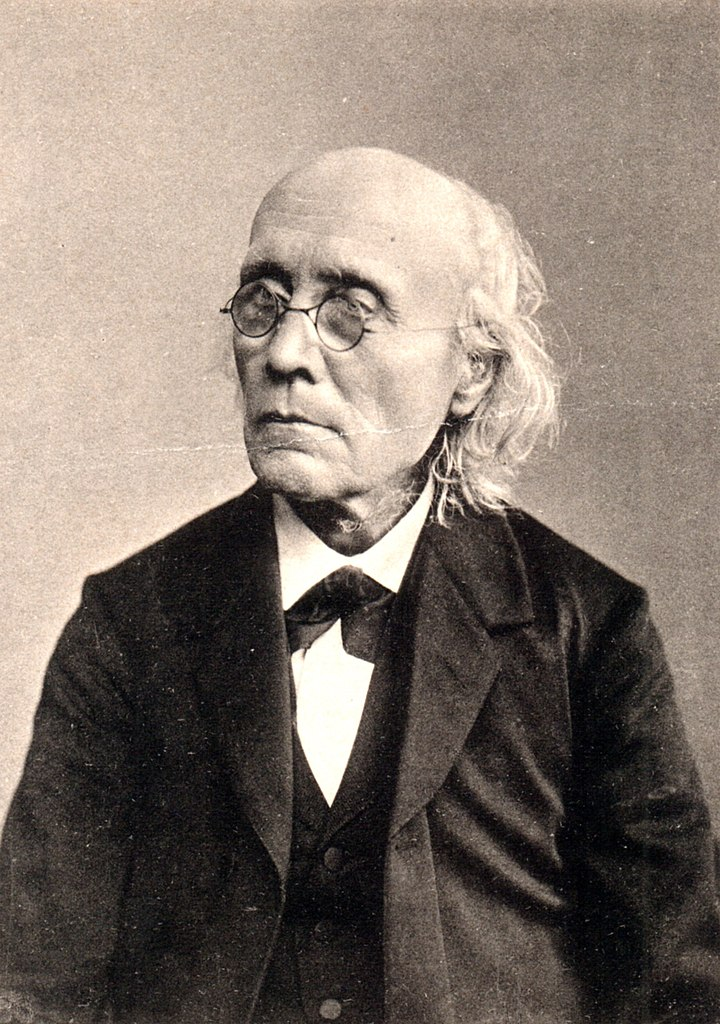

This weblog post is being published on Fechner day, 2024-10-22. It celebrates the day in 1850 when Gustav Fechner decided not to waste his life sleeping, and to make lasting contributions to psychophysics or, as some people call it, experimental psychology. People who want a basic understanding of his life may prefer to read a Wikipedia article about him.

There are two reasons why Gustav Fechner has impinged on my life.

First, one of my children is a grapheme-colour synesthete where letters and numerals are perceived as inherently colored. Synesthesia, more generally, involves perception where stimulation of one sensory/ cognitive pathway leads to an involuntary experiences in a second sensory/ cognitive pathway. Other examples include people experiencing colours/ tastes/ odors, when listening to music.

John Locke (1632 – 1704), in 1690 reported a blind man who said he experienced the colour scarlet when he heard the sound of a trumpet. There is disagreement as to whether this described an instance of synesthesia or was simply metaphoric.

There are two types of synesthesia. 1) projective: when a person sees colors, forms or shapes when stimulated. It is the most commonly experienced, and most widely understood version of synesthesia. 2. associative: when a person feels a very strong but involuntary connection between the stimulus and the sense that it triggers.

For example, in chromesthesia (sound to color), a projector may hear a trumpet, and see a red circle in space, while an associator might hear a trumpet, and think very strongly that it sounds red.

The first medical account came from German physician Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs (1786 – 2014) in 1812. In 1876, Fechner sampled the general public to estimate the size of the population experiencing grapheme-colour synesthesia. A 2013 article in Scientific American puts the number of synesthetes at about 4% of the population.

I am also acquainted with Fechner in terms of three methodologies he developed for experimental psychology. These were developed to find out various thresholds for a population.

Method of limits. An ascending series of stimuli are presented, in which the intensity of a variable stimulus is increased by predetermined steps until it can be perceived on 50 per cent of presentations (for an absolute threshold determination) or until a difference between it and a standard stimulus can be determined.

Method of adjustment. A test person is given control of intensity levels of a stimulus and is instructed to adjust it to the level where it is barely discernible. An average is based on several trials.

Method of constant stimuli. Variable stimuli are presented in random order, with the objecting of finding the smallest intensity that can be detected involving absolute thresholds or the smallest difference from a standard stimulus that can be detected in the case of a difference threshold. Currently, correctly identifying 75 per cent of presentations for detection or discrimination is used to set limits.

What I find most interesting about Fechner is his nature, divided as it was between scientist and metaphysical philosopher. His career was an unsuccessful attempt to unite these sides.

On one side, Fechner was at heart a positivist, advocating observation and measurement in science. This encouraged an interest in phenomenology and verificationism in philosophy. On the other side, his interest in metaphysics demanded a comprehensive cosmology, unattainable through scientific investigation. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy asks, in its article about him, but fails to answer: How could he be both a cautious and sober scientist and a daring and imaginative metaphysician?

It acknowledges that these two sides represent conflicting approaches, romanticism and empiricism. Of particular importance to him were the writings of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775–1854), Lorenz Oken (1779 – 1851) and Henrik Steffans (1773 – 1845) , where the emphasis was on a larger picture. However, since he was a student of physics and physiology at the University of Leipzig, he was influenced by his mentors, Alfred Wilhelm Volkmann (1801 – 1877) and Ernst Heinrich Weber (1795 – 1878), engaged in the experimental psychology of perception.

Positivist writing include a two volume work: Elemente der Psychophysik (1860) = Elements of Pyschophysics, parts of which were translated by Herbert Sidney Langfeld (1912) about the relationship between the psychic and physical. Because it stressed the dependence of the mental on its physical expression and embodiment, Fechner’s philosophy of mind has been categorized as materialism. Metaphysically, he is classified as a panpsychist, someone who believes the cosmos is psychic. For a modern, logical proof of this see this Wikipedia article which contains a summary of Thomas Negel’s (1937 – ) work on Panpsychism originally published in Moral Questions (1979). Fechner published his work on the subject in: Nanna oder über das Seelenleben der Pflanzen (1848) and Zend-Avesta oder über die Dinge des Himmels und des Jenseits (1851).

Fechner believed that metaphysics should follow, not lead, the empirical sciences. He believed these to be autonomous, with a foundation independent of philosophy.

Any attempt to understand Fechner must come to terms with both sides of his personality. Many studies of Fechner are one-sided, emphasizing one side of him at the expense of the other. Indeed, the view supported by many modern philosophers is that Fechner’s philosophy is incomprehensible without knowing about his life.