At Cliff Cottage it is common to use the IATA airport codes to denote an airport location. YQX refers to Airlandia, sorry that suggested name from Ottawa was never used, Gander! The Crossroads of the World, in Newfoundland. A gander is an adult male goose. Before one thinks of some testosterone fueled bird, the term also refers to a naive person, a simpleton.

My parents married in 1942-08 in St. John’s. I believe they spent some of the war years living in Gander, with the RCAF, the Canadian air force. Most of the time I was simply told they were stationed in Newfoundland. My mother described her work as being a plane plotter, moving objects representing planes across a floor. I think this had to do with ferrying planes to Britain. My father, ultimately with the rank of squadron leader, was involved with airport construction, at Gander as well as Goose Bay. I am unsure how much time they actually spent in each of these places. However, they admitted to flying between airports on transport aircraft. I have so many unanswered questions.

I have finished reading Jean Edwards Stacey’s (? – ), Voices in the Wind: A History of Gander, Newfoundland (2014). History incorrectly describes the work. There are moments when there is a chronology of events in and around the airport, but much of the space is given to unedited reminiscences of former and current residents. It was written by a journalist, not a(n) historian.

This was not the only book about Gander that was purchased. While at the North Atlantic Aviation Museum, Darrell Hillier was in attendance, selling his book, North Atlantic Crossroads: The Royal Air Force Ferry Command Gander Unit, 1940 – 1946. We now have a signed copy of his book.

The museum, itself, was interesting, but with the technology looking so outdated, early to mid 20th century, at best; analogue devices, rather than digital.

The museum had a Canso on display. It had been used in Newfoundland as a waterbomber fighting forest fires. These were Catalinas flying boats, which were modified with landing gear, transforming them into amphibians. The Catalina dates from 1933 when the US Navy ordered it, and Consolidated Aircraft designed it. A prototype was first flown in 1935 or 1936 (sources vary) in San Diego Bay. It became the most successful and prolific flying boat with 4 051 built. These aircraft were used in WWII by the American, British and Soviet Air Forces. Many of these aircraft came through Gander on their way across the Atlantic. Consolidated Aircraft and its successor Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft (Convair) built 1851 of these in San Diego, California. An undisclosed number were made by Vickers in Montreal starting in 1941-06. In addition, the Canadian government awarded Canadian Vickers a contract to produce PBV-1 Canso amphibians (a version of the Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat) for the Royal Canadian Air Force. To speed Canso production, the government authorized construction of a new manufacturing facility at Cartierville Airport in Ville Saint Laurent, on the north-western outskirts of Montreal, and appointed Canadian Vickers to manage the plant’s operation; 240 PB2B-1 flying boats were made for the Royal Air Force (RAF) and RCAF patrol bomber squadrons, 55 PB2B-1A and 67 PB2B-2 planes were also built by Boeing Canada, at a facility located on Sea Island, in Richmond, British Columbia. The site has since been re-developed as the Burkeville residential area, named for former Boeing-Canada President Stanley Burke. The PBN-1 Nomad, a heavily modified Catalina, was built by the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, supplying 155 to the RAF and 138 to the Soviet Navy. Soviet Gidrosamolet Transportnii factory at Taganrog, Rostov Oblast, also built 27 Catalinas.

In Scandinavia, the most prominent incident involving these planes was the Catalina Affair in which a Swedish Air Force search and rescue/maritime patrol Catalina = TP 47 was shot down by Soviet MiG 15 fighters over the Baltic Sea in 1952-06-16 while investigating the disappearance of a Swedish Douglas DC-3A-360 Skytrain Hugin on a signals intelligence mission, 1952-06-13, later found to have been shot down by Soviet MiG-15s in Swedish waters. The DC-3 was found in 2003 and raised in 2004–2005. In Norse mythology, Huginn = thought (Old Norse) and Muninn = memory (Old Norse) are a pair of ravens that fly all over Midgard = the world, and bring information to the god Odin.

In terms of aircraft, I have always been fascinated with amphibians, especially the Grumman Goose, possibly because it was featured in The Islanders, a 24 episode television series shown from 1960 to 1961, with William Reynolds (1931 – 2022) = Sandy Wade, James Philbrook (1924 – 1984) = Zack Mally, Diane Brewster (1931-1991) = Wilhelmina Vanderveer = Steamboat Willy and Roy Wright (? – ?) = Shipwreck Callighen, about a one-airplane airline run by the first three principals listed, in the East Indies.

We stayed at another Steele hotel, Sinbad’s. In many ways it was the opposite of Glynmill Inn: a more modern design, a scimitar symbol, breakfast included. Inside, there was not much that exuded Arabia. I have always had a positive impression of Sinbad, the 8th century fictional mariner from Baghdad and the Abbasid Caliphate, who during seven voyages has fantastic adventures in magical realms. These became late additions to the Thousand and One Nights framing the fictional Persian king Shahryar, and the tales narrated by his wife Scheherazade.

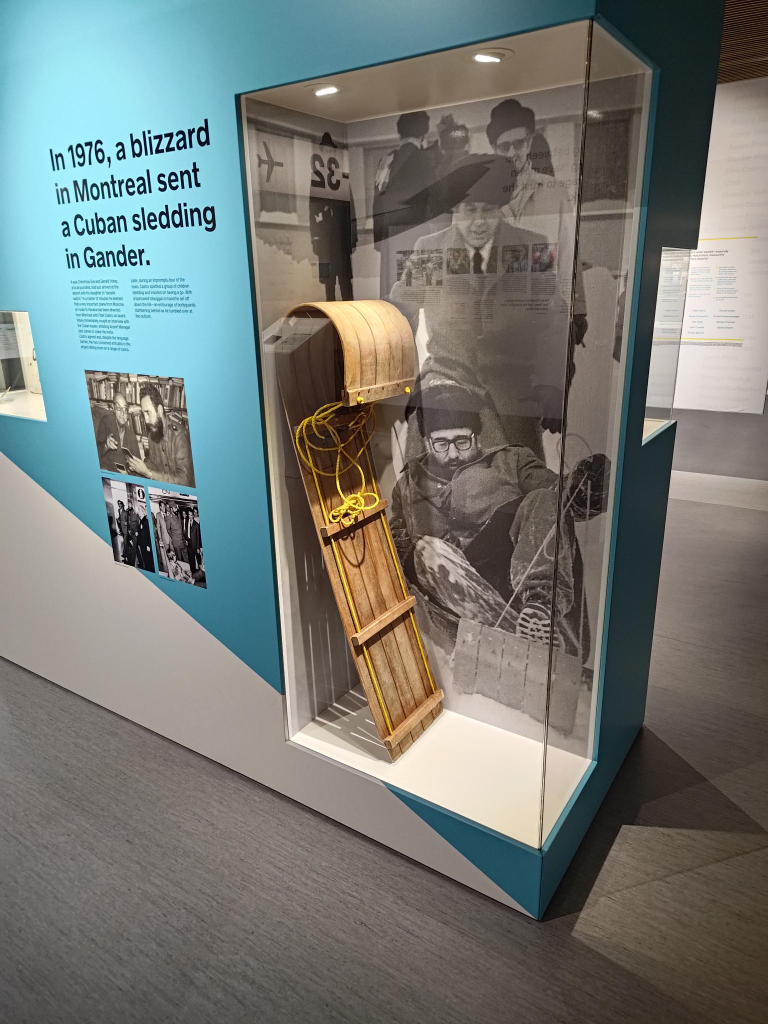

In the early evening we visited Gander airport. Above the main floor there was a display, showing its history.

The exhibits included a toboggan, and a story of Fidel Castro tobogganing in Gander.

At the airport there was a display of paintings by Barbara Brazil. This one, titled Fair Isle, Fogo attracted our attention. Yes, I am always fascinated by how light influences perception.