Institutional cinema’s mission is to pacify spectators. People congregate in a theatre or living room, but do not to act together or to talk to each other. They sit silently, in isolation. Institutional cinema is essentially a money machine. The public puts in money, directly (tickets) or indirectly (ads) and out pops entertainment.

Joyful Marmot Productions wants to change that cinema experience. Videos should not just be entertaining. There should be a more serious mission, social change. To do this, they have to be very aware of the pacifying qualities of institutional cinema, and other modes of representation that can be used.

André Bazin (1918-1958) regards the “myth of total cinema” as a desire of filmmakers to represent reality as completely as possible. This has resulted in many cinema innovations, including sound, colour, widescreen as well as editing techniques. It has not led to much social change.

Since 1914, the institutional mode of representation (IMR) has dominated film construction. Almost all contemporary films are IMR. Two other modes are the Primitive (PMR) used before 1914 and Deconstructionist (Here, DMR), which is used experimentally. There are others, but these three are sufficient to indicate alternative ways of construction and viewing. Within all three there are also many styles – some dominant, others less so.

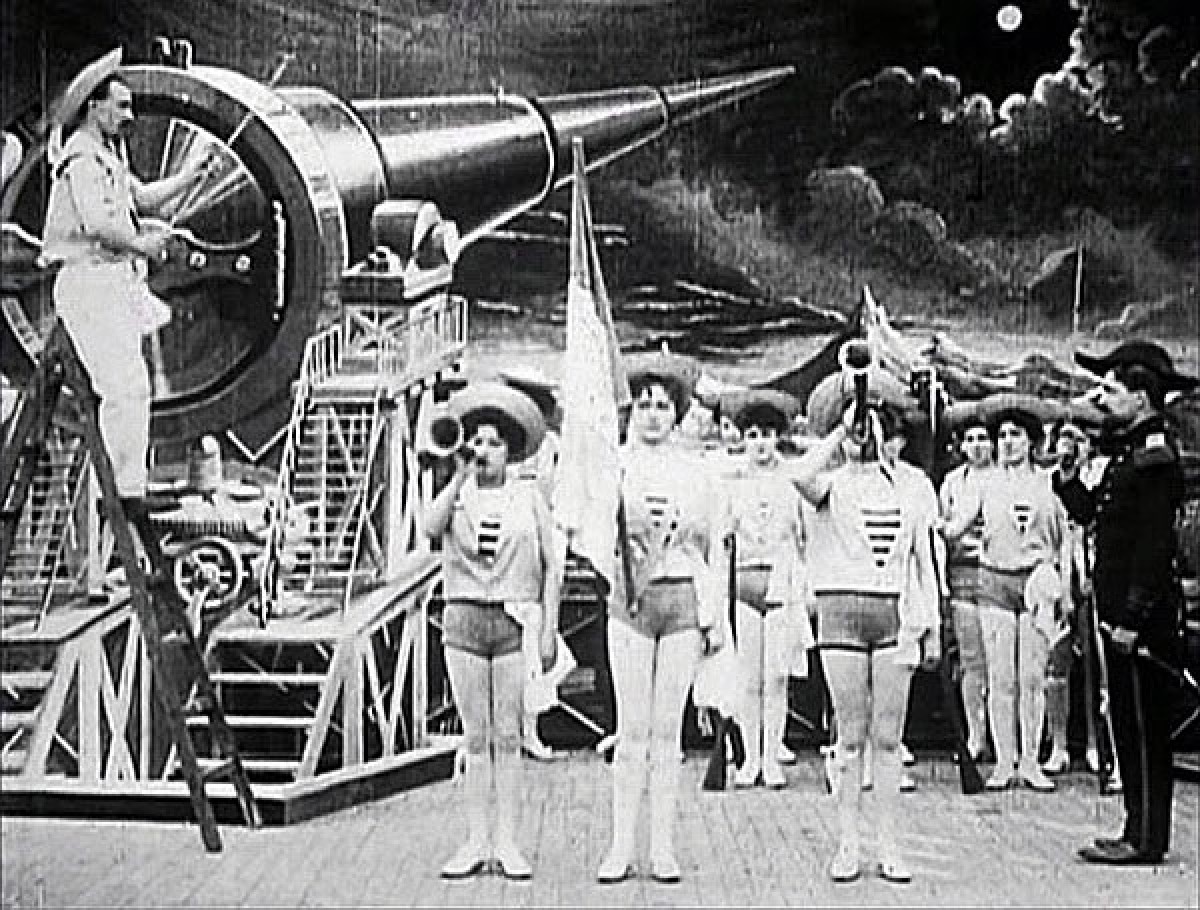

Noël Burch (1932-) presented the PMR concept in Praxis du cinéma (1969) [Theory of Film Practice (1973)]. PMR demands “autarchy of the tableau, horizontal and frontal camera placement, maintenance of long shop and centrifugality.” (p. 188) There are some big words, but what they mean is that one finds a (small) set, puts a camera in front of it, and starts filming. As was the case with Lumiere films, each shot ended when there was no film left in the camera. Another aspect of PMR: “It is as if story and characters were assumed to be familiar to the audience, or this knowledge was to be provided for them during the projection.” In the period prior to 1908, intertitles were used in silent film that eliminated any possible suspense. PMR was really only be used for serious subjects, often with punitive endings.

Burch’s focus is not PMR, but IMR. He argues that IMR is a bourgeois cinematic representation that creates an illusion of reality, an entirely closed fictional world on screen. Spectators are isolated physically to enhance their imaginative involvement. This contrasts with other modes where the film is an object for inspection. Burch notes that IMR is no more elaborate or realistic a system than its alternatives.

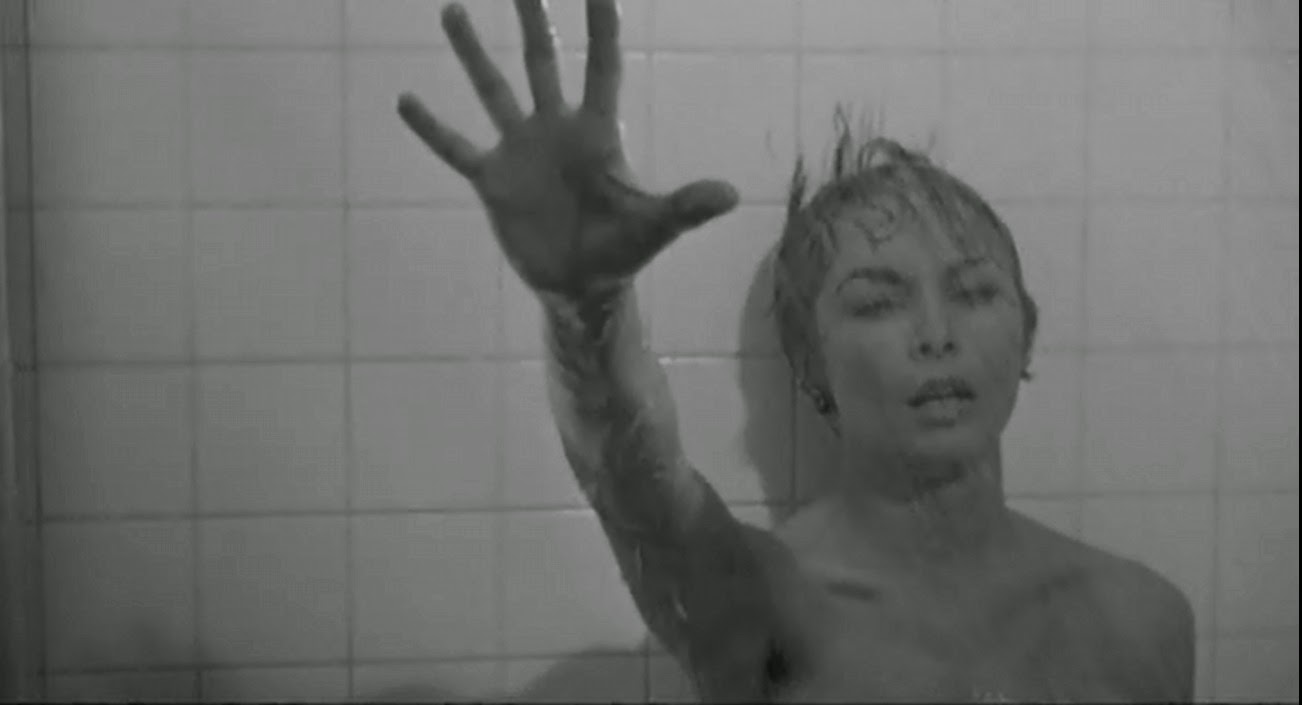

The key to IMR is the spectators identification with a ubiquitous camera. Various techniques (the “language of cinema”) were developed to accomplish this. First, films consist of a sequence of shots, each of which presents the spectator with one piece of information. Second, a 3D space is created. This involves rules of perspective, and cinematic techniques such as editing and lighting. Third, psychological depth is created. The narrative is driven by character psychology. Spectators are invited to interpret character motivations. Theatrical acting methods, and the psychological individualization of characters enhance this.

Close-ups are used in IMR, in contrast to PMR where they are lacking. To preserve the illusion of spatial integrity, which was lost with the introduction of close-ups, eye-line and directional matches were introduced.

Burch described other modes of representation, including the pre-WWII Japanese mode, discussed in: To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Cinema. (1979) [Pour un observateur lointain (1983)].

Moving on to a deconstructive mode of representation, one could begin philosophically by naming Jacques Derrida De la grammatologie (1967) [Of Grammatology (1976)], and the relationship between text (which in this context would include film) and meaning. I could, but I won’t, because what is needed is a more pragmatic deconstruction.

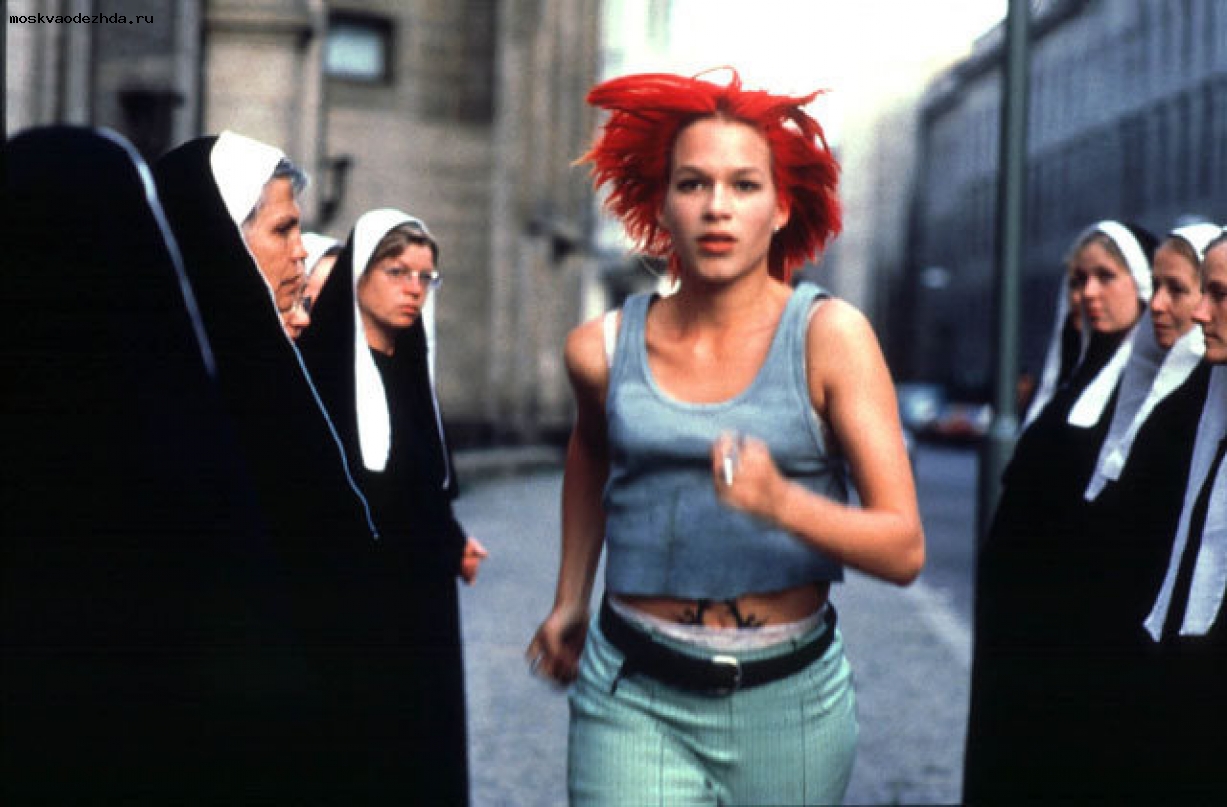

Tom Tykwer’s Lola rennt (1998) [Run Lola Run] is a good example of a deconstructive film. It consists of three iterations of a woman’s run (and associated actions) centering on her need to obtain 100 000 Deutsche Mark in twenty minutes to save her boyfriend’s life. Philosophically, the film comments on free will vs. determinism, the role of chance in people’s destiny, and cause-effect relationships. Flash-forward is used effectively.

Any films made by Joyful Marmot Productions will have elements of deconstruction in them.